Newspapers of the New Deal Concentration Camps

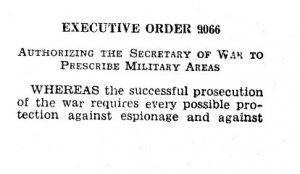

With Executive Order 9066, President Franklin Roosevelt created the War Relocation Authority (WRA) and authorized the mass incarceration of Japanese-Americans living in designated military areas

on the west coast. Roosevelt’s concentration camps were constructed and populated with a speed made possible in part by the magnitude of the American administrative state: the president’s New Deal had expanded both the power of the state, and its physical footprint across the nation. With the forced removal, detention, and subsequent incarceration of over 120,000 Japanese-Americans, one of the most repressive actions ever taken by the US government

, Roosevelt’s executive branch demonstrated its capacity to project state power on a hitherto unimaginable scale.1

Although the president’s order explicitly framed the internment as a military operation, and vested authority for its execution in the Secretary of War, the camps themselves were run by a largely civilian force, and, its name notwithstanding, the WRA became a division within the Department of the Interior. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that the Works Projects Administration (WPA) supplied the bureaucratic muscle for the WRA and its policy of mass incarceration. The WPA, long known for its innovative relief efforts, at first seems an odd choice from which to draw personnel for a strictly repressive, military-style operation, but Roosevelt’s concentration camps had much in common with the better known achievements of his domestic agenda, and historians have long noted this unsettling continuity.2

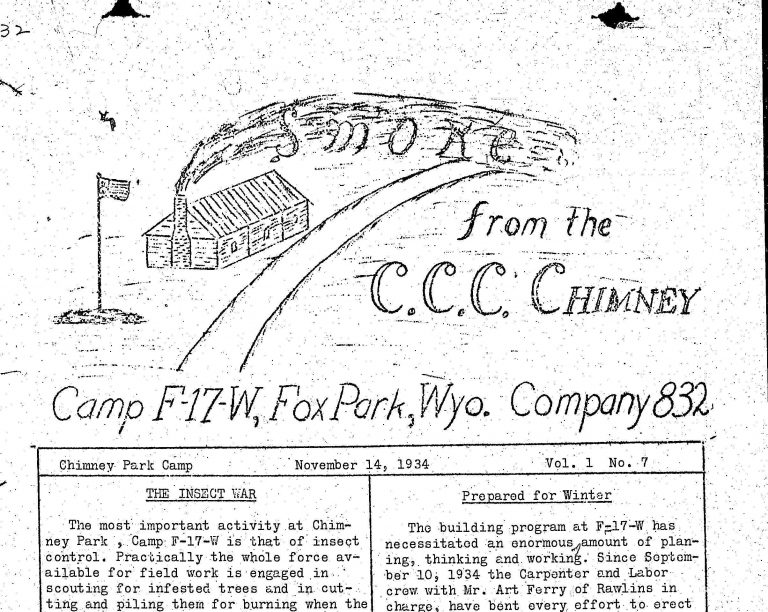

Furthermore, in implementing the policy of mass incarceration, Roosevelt’s WRA drew on more than just the human resources of the New Deal. Bureau of Reclamation project sites, along with Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps, were among the first locations scouted as candidates for possible conversion to incarceration facilities.3 In fact, the WRA, the Bureau of Reclamation, and the CCC all operated under the aegis of the Department of the Interior.

Of special and surprising significance, however, was a different New Deal legacy: the CCC camp newspaper. Journalism had, of course, been an important feature of several New Deal programs,4 but what distinguishes the CCC camp newspapers, and what arguably makes them the single most important antecedent to the internment camp newspaper, was the recognition by CCC administrators that a newspaper written and edited by the campers could actually be used as propaganda on the campers themselves.5 Not surprisingly, the CCC camp newspapers, with their inexpensively mimeographed appearance, bear more than a passing resemblance to the newspapers later published at Japanese-American internment camps:

The CCC camp newspapers seem to have been effective propaganda. Marlys Rudeen writes, As historial source materials, the papers display an ingenuous and hopeful face. The enrollees whose activities are documented here in word and picture were high-spirited, often (though not always) artistically talented, and, for the most part, enthusiastic about their new lives,

6 an assessment that could just as easily apply to the internment camp newspapers.

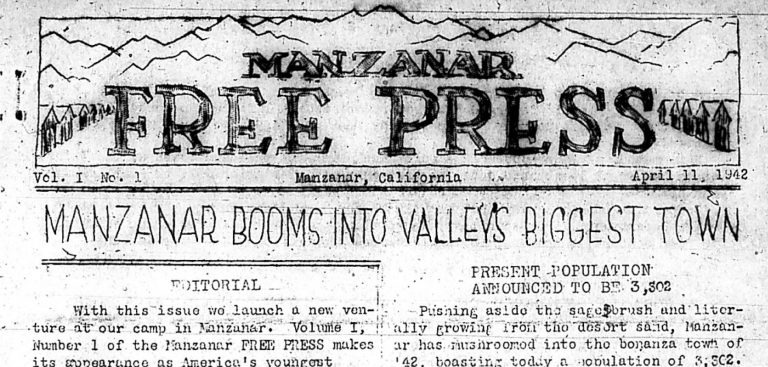

Congress cut funding for the CCC in 1942, and as the CCC camp newspapers, one-by-one, ceased publication, the internment camp newspapers began rolling off the presses. The first Japanese-American internment camp newspaper in the field was the Manzanar Free Press, the inaugural issue of which was published on April 11, 1942, less than two months after Roosevelt’s Executive Order:

Like the CCC camp newspapers, the internment camp newspapers were written by members of the camp, for members of the camp. Because the internment camp newspapers were written by detainees/prisoners, historians have speculated over the degree of freedom the editors enjoyed in conducting their papers. The official line was that the editors had almost complete freedom,7 and the first issue of the Manzanar Free Press assures its readers that it will have no editorial policy

(in scare quotes), but then goes on to describe what can only be called an editorial policy: Politics are out! We don’t have to worry about what our advertisers will think! We will have no circulation department worries

—all of which more accurately describes the state of affairs one would expect to obtain in a prison. And the editors obviously would not have circulation department worries because they had a literally captive audience.

The internment camps were supposed to be run as miniature democracies, and not just democracies, but American democracies. The free press (or at least the myth of one) had long ago been enshrined (codified, actually) as a cornerstone of American style democracy. Considered in this historical and cultural context, therefore, it makes complete sense—horrific irony notwithstanding—that the first internment camp newspaper would be named the Free Press. The camp newspaper editors often affirmed that they enjoyed such freedom.8 These affirmations form part of the boosterish quality one often finds in the camp newspapers, a quality that belies the hidden hand of censorship which must inevitably attend any attempt to publish a newspaper at gunpoint.

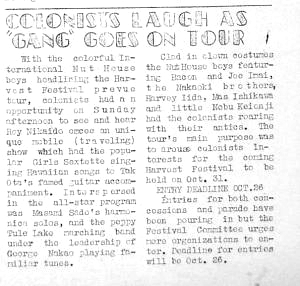

The internment camp newspapers helped manufacture the appearance of consent, which could in part explain why the WRA was so adamant that these newspapers be published at all. In many cases, a camp’s newspaper was up-and-running before the camp itself had even been completed.9 That the newspapers were to some extent successful in this coercion of consent can be seen, for example, in the consistently cheerful tone of the articles, which tended to focus on the positive aspects of life inside the camps:

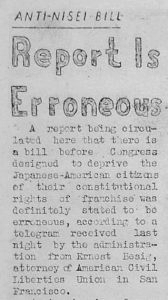

The newspapers also served to dispel rumors that had the potential to create unrest:

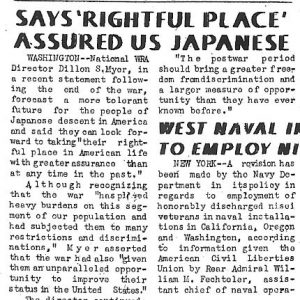

And they tended to publish news that promoted the most favorable possible interpretation of the government’s actions, as in this article, in which the National WRA Director astonishingly claims that the war has given Japanese-Americans an unparalleled opportunity to improve their status in the United States

, and that The postwar period should bring a greater freedom from discrimination and a larger measure of opportunity than [Japanese-Americans] have ever known before

:

In the final, “Souvenir edition” of the Mercedian, the camp manager wrote, on behalf of the administrative staff

, that We can do no less than admire the spirit, the morale, and the attitude of this community. The ability and the willingness of residents to do effectively and readily most of the actual work connected with the business of taking care of each other has made the responsibility for the operation of this Center a comparatively light responsibility. It has made our job easy when it might have been hard. It has given us pride and satisfaction when it might have given us shame and regret. It has reflected credit on us when it might have reflected discredit

(emphasis added).10

The internment camp newspapers—written, edited, and read by the Japanese-American prisoners—demonstrate how ideology can make the objects of state power ultimately consent to, and even collaborate in, their own subjugation. As the camp manager at Merced California wrote, the detainees themselves performed most of the actual work

, and their cooperative spirit made our job easy when it might have been hard

. One would be hard pressed to find a better exemplar of Foucault’s argument that the perfection of power should tend to render its actual exercise unnecessary [….] the inmates should be caught up in a power situation of which they are themselves the bearers.

11 Roosevelt’s concentration camps yoked the repressive state apparatus with the ideological state apparatus, an imposition12 of state power artefactually preserved in the internment camp newspapers, which form part of the camps’ legacy.

The best digital collection of internment camp newspapers can be found at the Densho Digital Repository.

Notes

1. Alison Dundes Renteln, "A Psychohistorical Analysis of the Japanese American Internment," Human Rights Quarterly 17, no. 4 (November, 1995), 618. For much more on how Roosevelt’s New Deal made possible the rapid implementation of his mass incarceration policy, see Jason Scott Smith, "New Deal Public Works at War: The WPA and Japanese American Internment," Pacific Historical Review 72, no. 1 (February, 2003): 63-92. Connie Y. Chiang writes, The New Deal and its social and conservation policies proved to be central to the administration of the WRA [War Relocation Authority]

, in "Imprisoned Nature: Toward an Environmental History of the World War II Japanese American Incarceration," Environmental History 15, no. 2 (April, 2010): 236-267. See also: Thomas James, "The Education of Japanese Americans at Tule Lake, 1942-1946," Pacific Historical Review 56, no. 1 (February, 1987), 25-58.

2. Jason Scott Smith, A Concise History of the New Deal (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 163-164.

3. Robert Wilson, "Landscapes of Promise and Betrayal: Reclamation, Homesteading, and Japanese American Incarceration," Annals of the Association of American Geographers 101, no. 2 (March, 2011): 424-444; and the Oregon State Archives, "Not Exactly Paradise: Japanese American Internment Camps," Life on the Home Front: Oregon Responds to World War II, 2008, (accessed February 27, 2017).

4. Perhaps the most famous were the photojournalists of the Farm Security Administration (FSA), later restyled the Office of War Administration (OWI). See: Gilles Mora and Beverly W. Brannan, eds, FSA: The American Vision (New York: Abrams, 2006), and: Michael Lesy, ed., Long Time Coming: A Photographic Portrait of America, 1935-1943 (New York: Norton, 2002). Journalism and journalists also played an important role in the Federal Writers' Project. See David A. Taylor, Soul of a People: The WPA Writers' Project Uncovers Depression America (Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley and Sons, 2009).

5. Wayne Stewart Yenawine, "Civilian Conservation Corps Camp Newspapers: A Checklist of Papers Published before July 1, 1937, with Bibliographical and Other Notes" (master's thesis, University of Illinois, 1938), 2.

6. Marlys Rudeen, The Civilian Conservation Corps Camp Newspapers: A Guide (Chicago: Center for Research Libraries, 1991), v.

7. See: Takeya Mizuno, "The Creation of the 'Free' Press in Japanese American Camps: The War Relocation Authority's Planning and Making of the Camp Newspaper Policy," Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 78, no. 3 (Autumn, 2001), 503-518.

8. John Stevens, "From behind Barbed Wire: Freedom of the Press in World War II Japanese Centers," Journalism Quarterly 48, no. 2 (Summer, 1971), 279-287.

9. Takeya Mizuno, 504-505

10. Harry L. Black, "Mgr. Black Greets Residents: Good Luck!" The Mercedian, August 29, 1942, [1].

11. Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage Books, 1979), 201.

12. Play on words intended. Actually, only two of the camp newspapers were printed using traditional letter press machines; the rest were printed on mimeograph machines. Both methods, however, involve the use of physical force to impress letterforms and line drawings onto paper. In the case of the mimeograph machine, the ink is pressed through stencils onto the paper. See James Mosley, "The Technologies of Print," in The Oxford Companion to the Book, ed. Michael F. Suarez, and H. R. Woudhuysen (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

Bibliography

Chiang, Connie Y. "Imprisoned Nature: Toward an Environmental History of the World War II Japanese American Incarceration." Environmental History 15, no. 2 (April, 2010): 236-267.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York: Vintage Books, 1979.

James, Thomas. "The Education of Japanese Americans at Tule Lake, 1942-1946." Pacific Historical Review 56, no. 1 (February, 1987): 25-58.

Lesy, Michael, ed. Long Time Coming: A Photographic Portrait of America, 1935-1943. New York: Norton, 2002.

Mizuno, Takeya. "The Creation of the 'Free' Press in Japanese American Camps: The War Relocation Authority’s Planning and Making of the Camp Newspaper Policy." Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 78, no. 3 (Autumn, 2001), 503-518.

Mora, Gilles, and Beverly W. Brannan, eds. FSA: The American Vision. New York: Abrams, 2006.

Mosley, James. "The Technologies of Print." The Oxford Companion to the Book. Edited by Michael F. Suarez and H. R. Woudhuysen. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Oregon State Archives. "Life on the Home Front: Oregon Responds to World War II." Accessed on February 27, 2017.

Renteln, Alison Dundes. "A Psychohistorical Analysis of the Japanese American Internment." Human Rights Quarterly 17, no. 4 (November, 1995): 618-648.

Rudeen, Marlys. The Civilian Conservation Corps Camp Newspapers: A Guide. Chicago: Center for Research Libraries, 1991.

Smith, Jason Scott. A Concise History of the New Deal. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

----. "New Deal Public Works at War: The WPA and Japanese American Internment." Pacific Historical Review 72, no. 1 (February, 2003): 63-92.

Stevens, John. "From behind Barbed Wire: Freedom of the Press in World War II Japanese Centers." Journalism Quarterly 48, no. 2 (Summer, 1971): 279-287.

Taylor, David A. Soul of a People: The WPA Writers' Project Uncovers Depression America. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley and Sons, 2009.

Wilson, Robert. "Landscapes of Promise and Betrayal: Reclamation, Homesteading, and Japanese American Incarceration." Annals of the Association of American Geographers 101, no. 2 (March, 2011): 424-444.

Yenawine, Wayne Stewart. "Civilian Conservation Corps Camp Newspapers: A Checklist of Papers Published before July 1, 1937, with Bibliographical and Other Notes." Master's thesis, University of Illinois, 1938.