Drown It Slowly and See: Rural Childhoods in Print

Historians sometimes use bookseller stock lists (or catalogs) to reconstruct, through inference, the cultural climate of a place and time,1 and farm newspapers published such stock lists, as well as book advertisements. Sometimes a farm newspaper would publish lists of books for sale through its office. Booksellers also bought space in the farm newspapers to advertise the books they offered for sale. The practice of publishing book lists gradually ceased in the 1910s, presumably as Rural Free Delivery made it easier for booksellers to distribute full catalogues through the mail, rather than having to buy expensive advertising space for abbreviated stock lists.

Even as booklists disappeared from the farm newspapers, books remained a presence in the form of advertisements. As a kind of collateral evidence, these advertisements must be treated carefully. They do not necessarily tell us what Midwestern farm families actually read, much less how they used what they read. They don't really even tell us what books farm families bought. The advertisements probably reveal what booksellers believed farm families might want to read, or what booksellers believed farm families ought to read. Maybe they reveal the kind of books that farm families wanted to have on their shelves, as prestige objects. In at least some cases the booksellers must have been pushing overstock. One can, however, safely conclude that the advertisements are evidence of books that once existed, which is valuable evidence indeed, especially if the book today is scarce or no longer extant: in such cases, the advertisements and book lists might supply the only evidence of these books' existence, as well as a means of identifying fugitive publications.

One such book is The Art of Trapping by Alphonso "Fair and Square" Shubert (1852-1926). Shubert would probably never have expected his trapping manual to become a rare book, but a century after its publication it survives in only a few original copies, and serves as an exemplar of the trapping guidebook, a genre that, at one time, was advertised heavily in farm newspapers and probably circulated widely throughout the rural Midwest. Today, an abundance of contemporary advertising supplies the only real evidence of these publications' apparent ubiquity and popularity.

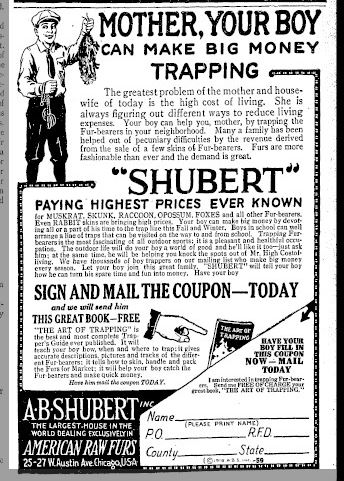

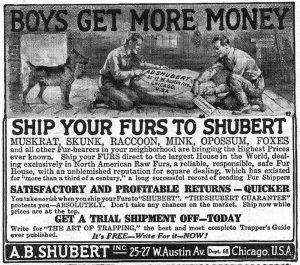

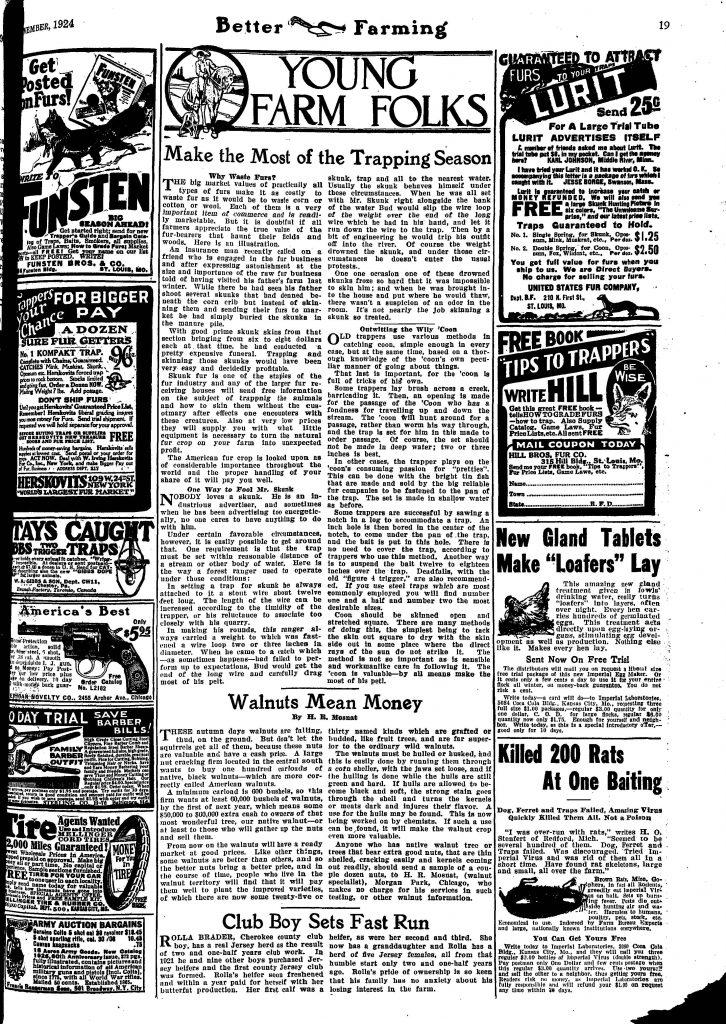

By the 1910s, the trapping guidebooks were being produced in large numbers by raw fur houses, as a way to bring the raw fur market from the cities, where most raw fur wholesalers were located, to the country, where the wholesalers obtained their actual supply. The raw fur houses were major advertisers in the Midwestern farm newspapers, as can be seen on this page of Better Farming, where all advertising space has been taken by raw fur houses:

Note that the raw fur houses were not advertising to sell furs, but to buy them from rural trappers. These advertisements were really solicitations for piecework labor,2 a common type of advertising in farm newspapers: urban businesses, eager to exploit the surplus labor capacity of farm women and children, touted the supposed ease of earning extra money in one's spare time. Opportunities ran the gamut from selling postcards to raising chickens, from creating window show cards to milling flour in the home. The winter—prime trapping season—was a comparatively slow time in the Midwestern farm calendar, and fit well into the familiar piecework pitch:

In the above advertisement, Shubert encourages mothers to get their children started in the trapping business by sending for a free copy of his book. The guidebook was in part an instruction manual, but it also served as a means of broadening the base of potential clients by promoting trapping as an ideal activity for children as well as adults.

Reading through The Art of Trapping, with its emphasis on personal character, honor, cleanliness, honesty, strength, safety, achievement, and outdoorsmanship, one can't help but note the similarities to the virtues espoused by the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) in their Official Handbook for Boys, which debuted just six years earlier, in 1911, about the same time the fur houses began heavily advertising trapping manuals to children. Prior to 1910, very few firms advertised trapping manuals specifically to children. A keyword search in a digital collection of major Midwestern farm newspapers located only one, and this firm's advertisements appeared in 1870.3 Forty years later, however, dozens of raw fur houses suddenly began marketing to children. The available evidence suggests an interesting correlation: the aggressive advertising of trapping manuals to children seems to have coincided with the emergence of the BSA.

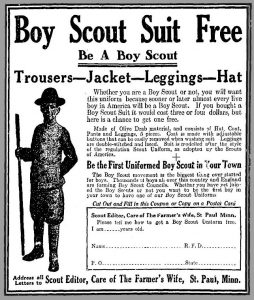

For all the similarities, however, The Art of Trapping is perhaps more notable for the ways in which it differs from the BSA's Official Handbook for Boys. As historians have shown, the BSA was primarily an urban, middle class organization, both in membership and ethos, developed in response to the perceived crisis of urbanization in America. Its leaders envisioned the organization as an instrument of social control over the rapidly growing population of unsupervised urban youth.4 In contrast, The Art of Trapping and similar trapping guides were written for poor, rural audiences. The BSA actually had some difficulty gaining traction in rural areas, and its presence in the farm newspapers is often felt rather weirdly as a kind of absence, or negative presence:

The above advertisement, almost a discursive cipher, argues that Whether you are a Boy Scout or not, you will want this uniform […] Be the First Uniformed Boy Scout in Your Town

. Similarly, in "The Boy Scouts of the Farm: How Farm Boys Can Join a Great Movement by Becoming Pioneer Scouts" (Farmer's Wife, February 1920), the author explains that, while Some farm boys still think that scouting is exclusively a city activity,

the farm boy can still join the Boy Scouts as part of a special division called Pioneers, who are basically Boy Scouts without a troop or, in his words, scouts who go it alone.

In short, the Pioneer Scout endures all the same tests as other Boy Scouts, but enjoys none of the camaraderie. The article highlights an often forgotten aspect of rural life: how horribly isolating it could be.

Perhaps the strongest connection between Scouting and the country was ideological: The BSA leaders posited a nostalgic fantasy of country life as an antidote to the supposedly deleterious influence of the city on America's middle class youth. The BSA's idealized fiction of country life proved to be not only untrue, but also, ironically, in ideological conflict with the reality, which can be seen in part through the way in which the BSA responded to the popularity of trapping in the countryside. Although the BSA accepted advertising from the raw fur houses (including Shubert's—see below) in its magazine, the organization was never able to reconcile the brutal reality of trapping with the more ethereal values of Scouting.

In a tortuously reasoned article from the November, 1918 issue of Boys' Life ("The Ethics of Trapping"), the author struggles to explain how the steel trap and the Boy Scout law can be brought into a state of real harmony.

The author repeatedly acknowledges the cruelty of trapping, explaining that he himself found trapping so repulsive that I never have practiced it

:

No real scout will permit a fox or skunk or any other animal to linger in the jaws of a trap any longer than is necessary. Moreover, he never will cause animals any needless pain, and will kill them instantly […] Every living creature, tame or wild, has a certain series of God-given rights which honorable people are bound to respect.

The author then takes aim at the hawkers of trapping manuals, pointing out that, contrary to the raw fur houses' claims, there is no easy way to make money from trapping: Let no scout make the mistake of thinking that fur trapping, even the humblest kind, is a simple business, or easy to learn […] every boy who seeks to become a trapper can best learn the ins and outs from a living teacher,

an implicit and invidious comparison to those boys who were learning from a manual. The author concludes, I do not believe that any boy can engage in trapping professionally without a decided dulling of his fine and chivalrous feelings towards the weak and helpless, and a certain lowering of his high ideals. In fact, how can any scout become a professional steel-trap trapper and live up to the Boy Scout law?

In short, despite his best rhetorical efforts, he concedes that trapping ultimately cannot be reconciled with the Boy Scout ethos.

The raw fur houses were also selling a lifestyle and an ethos, but one better adapted to the hard realities of rural life. Shubert's Art of Trapping was almost a counter-manual to Scouting. Sure, The Art of Trapping drew upon many of the same virtues, but it counseled the boy to use these virtues in the service of self-interest, rather than in the service of the community. Other contrasts are far grimmer: whereas the Scout is charged with the conservation of nature, the trapper must learn to battle nature, often portrayed as an enemy in the form of pests that must be exterminated. By happy coincidence, the furs of these same pests were worth money. In The Art of Trapping, Shubert asks,

Does the average farmer stop to think about the thousands and even millions of dollars that are paid out every year by the large Fur houses for the skins of the 'farm yard pests?' The Weasel, a menace to the chicken coop, the Skunk, Muskrat, Raccoon, Mink, and other fur bearing animals classed as 'varmints' and considered a nuisance to the crops—all have their intrinsic value, and it would be well for many to forget the nuisance end of the story and look at the profit side.

The Official Handbook for Boys, in contrast, placed kindness to animals among the cardinal virtues, and kindness to animals was a virtue the boy trapper could ill afford to indulge. The raw fur houses borrowed the vernacular of Scouting, but used it towards very different ends: the challenge of the hunt, the frisson of the kill, became the activities that that could best thrill the rural boy's imagination:

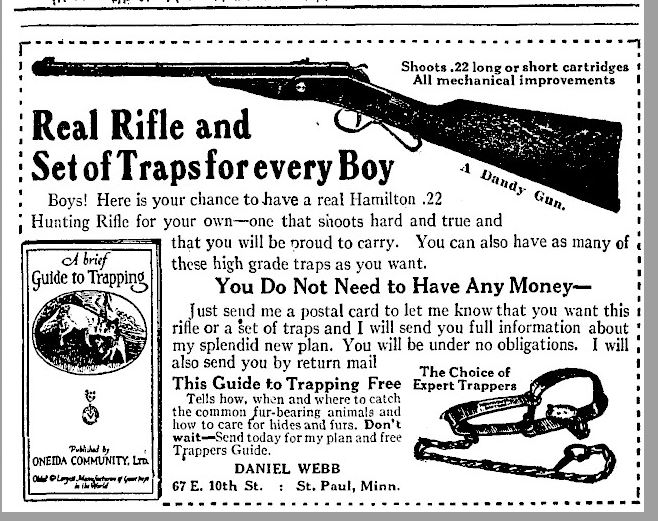

Real Rifle and Set of Traps for every Boy [...] You can also have as many of these high grade traps as you want.Common advertisement in the Farmer's Wife.

The advertisements demonstrate how trapping, while essentially a form of piecework, was sold to children as an activity of fun and adventure. The trapping manual itself, often lavishly illustrated, helped foster this more fanciful aspect.

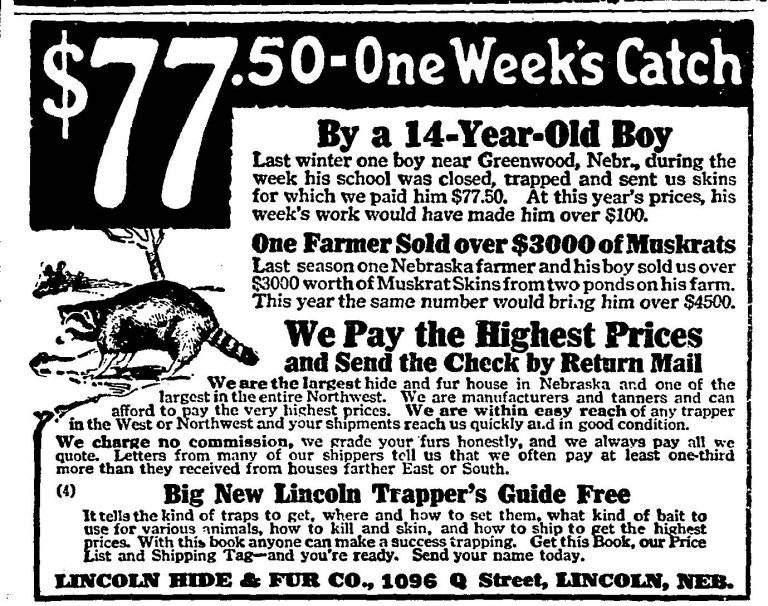

Though few copies of Shubert's book have survived, it was far from unique in its time. Dozens of raw fur houses issued some kind of "start-up guide" to trapping for children. Examples include the Lincoln Trapper's Guide from the Lincoln Hide and Fur Company, and Tips to Trappers from Sears, Roebuck and Company:

These publications are today either non-extant, or else very rare, so that the advertisements provide both a means of identifying such publications, as well as evidence that they ever existed in the first place. The advertisements also supply valuable context that would likely be missing from the manual itself. For example, it's unclear from a direct examination of The Art of Trapping that it was intended for children, while the advertisements make this intention quite explicit. Thanks to the advertisements, therefore, we not only know about these manuals, but we also know that through the manuals the raw fur houses specially recruited children as pieceworker laborers. In addition to advertisements for trapping guides, the farm newspapers also printed original articles for children on trapping:

Farm newspapers help document the cultural and economic relationship between urban and rural America, at precisely the moment when the nation's population was beginning to shift from predominantly rural to predominantly urban.5 The traffic in furs seems an especially apt example of this fraught relationship because, although trapping is not technically an extractive industry, it shares with extractive industries the quality of depleting the natural resource upon which the industry depends, and also because there's a wanton violence to trapping that vividly captures the exploitative relationship between the growing urban markets and the hinterlands that supplied those markets with essential raw materials. Here, for example, is Shubert's advice on how actually to kill a trapped animal:

Another way is to drown the animal, if there is water nearby. Fasten the trap to the end of a long pole, ten to twelve feet in length. When the animal is caught, approach carefully and pick up the pole. By moving very slowly and making no quick motions, the animal can be led to the nearest water, where it can be drowned. Lift the animal up easily and let it down into the water, pushing the pole down until the animal’s head is drawn under. Hold it under water until nearly drowned, then let it up to breathe, and push it under again, keeping it there until dead.

The farm newspapers of the 1910s are filled with advertisements and articles for children on how to trap fur bearing animals. The sheer volume of copy devoted to trapping suggests that it was an important part of the rural Midwest's social, economic, and environmental history, and the farm newspapers supply important documentation of this history.6

Notes

1. Archer Taylor, Book Catalogues: Their Varieties and Uses (Chicago: Newberry Library, 1957).

2. Thank you to Mary Stuart for drawing my attention to the similarities between fur trapping and piecework labor, as well as the continued role of cottage industry in the rural economy.

3. The keyword search was done in the digital collection Farm, Field, and Fireside. The advertiser was not even a raw fur house, but a mail-order bookseller called Hunter and Company. There’s an odd coda to the story of Hunter and Company: three years later the owners were arrested for sending obscene literature through the mails. They plead guilty, and were fined $560.

4. David I. Macleod, "Act Your Age: Boyhood, Adolescence, and the Rise of the Boy Scouts of America," Journal of Social History 16, no. 2 (1982), 3-19; Ben Jordan, "'Conservation of Boyhood': Boy Scouting’s Modest Manliness and Natural Resource Conservation, 1910-1930," Environmental History 15, no. 4 (2010), 612-42..

5. Timothy B. Spears, Chicago Dreaming: Midwesterners and the City, 1871-1919 (Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 2005).

6. Histories of trapping in the Midwest typically begin and end with the coureurs de bois of the early modern period.