Silence

This essay is a brief memoir of grade school life, from the fall of 1980 to the spring of 1985. Like many memoirs, this one is part origin story, and part apologia. Fundamentally self exculpatory in nature, it should be regarded with skepticism, this very warning itself a gambit, calculated to win your trust with its disarming candor, my supposed self-awareness a guarantee of good faith and also evidence of my ability to sift the self-serving from the true, and most of all evidence of sincerity, that cynosure of white Protestant prose style. Impossible but mandated sincerity! One reason why writers like Oscar Wilde and Isak Dinesen were, later in life, such a revelation to me.

I grew up in a small town on the long, flat stretch of farmland of north central Illinois: 100 miles from Wisconsin, 100 miles from Indiana, and seventy miles from Iowa, “in the middle of nowhere.” A north/south trail used by early white settlers traveling from Peoria to the lead mines at Galena ran through my town, as did an east/west trail used by Sauk Indians traveling between Rock Island and the British trading posts at Detroit. A valley five miles to the south is an abandoned riverbed where, according to geologists, the Mississippi River once flowed, before a glacier pushed it into its current channel seventy miles to the west.

The town, rather unimaginatively named Princeton, had one stop light, at the intersection of Main Street and U.S. Route 6, the latter being an old, two-lane, transcontinental highway. Growing up, I had little notion of this road leading any farther east than La Salle, and later in life I was surprised to encounter it once again, a couple miles south of the college in Connecticut where I attended graduate school. Route 6 is the highway that Sal Paradise takes through Illinois on his first trip across the country, in Jack Kerouac’s novel, On the Road, so he would have driven through my town, though it doesn’t garner a mention.

Princeton had a population of 7,300 and was by far the largest town in the county. It was what people would call “in the country” or “in the countryside,” but that expression could be a little misleading if you weren’t from there. To me, there was nothing pastoral or idyllic about the country, and the expression did not imply nature or wilderness. Quite the contrary: the north central Illinois countryside is among the most cultivated land in the world, but it’s all in corn and soybeans, platted out with scientific precision and arrayed into perfectly symmetrical rows. Our countryside felt sterile as a laboratory, and in some ways it really was a giant laboratory for Pioneer Hi-Bred International, at that time the largest producer of corn and soybean hybrids in the United States. So the intensive cultivation notwithstanding, nobody would really think to describe the region as cultivated. The land was astonishingly fertile, but it felt hopelessly barren, one of many paradoxes that don’t feel fanciful enough even to qualify as paradoxical, and if paradox is essentially a form of contradiction, then the countryside was practically an anti-paradox, since the purpose of hybridizing corn was to produce entire fields of completely identical corn plants. A common early-summer job for children was deroguing, which was the process of going through the fields and removing “rogue” corn, rogue corn being any corn plant not completely identical to all the others. When thinking of my town, therefore, you must banish from your imagination any idea of the picturesque or the bucolic: it’s the “fly-over-country” of fly-over-country. You felt deprived of both the civilization enjoyed by city dwellers, as well as the natural beauty people often associate with the countryside. Largely isolated from both civilization and nature, in a time long before the World Wide Web, your main connections to the outside world were radio and network television, all beamed in from either Peoria or the Quad Cities.

I began kindergarten at Jefferson Elementary School in 1980. That fall, the Weekly Reader held a mock presidential election. I voted for Jimmy Carter because I thought his face better-looking than Reagan’s. Contemplating that memory makes me wonder if innocence isn’t really a kind of radical superficiality. If so, then I was very innocent indeed.

Kindergarten was largely an education in disposition. Contemporary experts said that “children in kindergarten are concrete in their thinking; they like to count, arrange, and handle,” with “arrange” being the most salient feature of my own kindergarten education: you learned to position yourself in relation to this new institution you were joining: school, the concrete fact of your new existence. There was nothing abstract about school at this age, and you regarded your classmates more as concrete attributes of school than as people with whom you could have friendships. I do not remember thinking of my relationships with classmates as friendship until about third grade. Of course, we used the word “friend,” but really it just meant people in your class, more things to be arranged, counted, and handled. In kindergarten you had to memorize information like your home telephone number and your home address, because those facts identified the second point in the axis that, going forward, would define your life: school and home. We also learned to tie our shoes using a toy wooden shoe. (A couple years later, when Velcro shoes became “all the rage,” my mother would not let us have them because she said they were for children who didn't know how to tie their own shoes, by which I clearly understood her to mean “slow children.”) In kindergarten, you began learning “to hold your own,“ but were never told what “your own“ actually was. It strikes me now that much of what we learned in kindergarten was really about brute survival, and that brute survival is often a matter of disposition, which would explain why so many animals simply cannot survive in captivity: they lack the disposition to do so.

Probably the most important disposition I learned in kindergarten was inadequacy, or resentment—I can never really distinguish the one from the other, but it formed slowly in me, like a pearl, around the daily irritation of nap time: each day at a certain time we retrieved our braided rugs from our assigned cubby holes, and we took a short nap. I liked the actual napping, but when nap time was over the teacher would choose the student who had behaved the best during nap time, and that student got to awaken all the other students with a magic wand, a wooden stick with a painted star attached to the top. Over the course of that entire school year—more than 150 days and 150 naps—she never once chose me to wake the other students with this magic wand that had clearly captured my imagination, and I resented the snub. Beginning then, I developed a brilliant talent for resentment.

Above our kindergarten teacher’s desk hung a wooden paddle. On the first day of school she explained that this paddle would be used to spank children who misbehaved. I suppose it’s evidence of a certain progressivism in the era, that the teacher had to explain its purpose at all. I have to imagine that in earlier times no child needed to have a paddle’s purpose explained to him. I don’t remember the teacher ever using the paddle; it just hung there above her desk, a minatory symbol of what might happen.

After kindergarten, no other teacher had such a paddle, at least not one on display, although my fourth grade teacher merrily teased that, in her closet, she kept a “wet noodle,” which, like the paddle, could be used on bad students. I always assumed this wet noodle was some kind of joke, though I never really understood the joke. All joking aside, however, this same teacher was capable of truly sadistic approaches to discipline. One of our classmates, Danny Bird, had a behavior disorder, or at least that’s what I believe they called it at the time. The fourth grade teacher was forever having trouble with him. One morning, as we entered the classroom, we beheld a most astonishing thing: the teacher had taken a refrigerator box, and had cut it up to resemble a jail cell. She had placed this box over Danny Bird’s desk, and she called it his “bird cage,” a cruel pun on his last name. Whenever he left his desk, she would say, “Fly back to your bird cage, Danny.”

In first grade there was a girl who believed she was an Indian princess. She wore fringed buckskin trousers and matching tunic with fancy beadwork. She also wore a beaded headband with a feather fixed to the back. She sat “Indian style” all day long in her desk, with upper arms extended parallel to the ground, her forearms crossed one over the other. I was amazed she had the strength to maintain her arms in this position for so long. If the teacher called on her, she would raise her right forearm, and, with complete conviction, answer the teacher by saying, “How.” She did not return to our school for second grade. I wondered where she went.

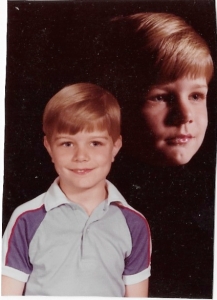

Each year a professional photographer established a makeshift studio in the school library, and all the students would have their official school portraits taken. There was a brief fashion in school portraiture for double exposure, in which a second, ghost image of the subject hovers in slight profile above the frontal shot. Here was my portrait:

This type of portrait always seems a little eerie to me, as though the subject’s shadow-self had been magically captured by the camera.

The photographers made their money not by taking your photograph, but by selling copies to your parents. These copies came in almost every conceivable size, some sizes suitable for framing, others perhaps for a bulletin board at the parent's workplace. Parents would typically distribute copies to all your relatives. Our family did not have many relatives, but I think my grandmother received a new supply of these photographs every year, and she proudly displayed them in her home.

Almost every parent bought a dozen or so of these school portraits in a format that probably no longer exists: the “wallet-sized.” Back then, wallets came with miniature, clear plastic photo albums, and parents would carry their children’s school portraits in these mini-albums, so that they would always have a picture of you to show their friends and associates, or perhaps just to gaze upon in their more sentimental moments. I suspect the super-abundance of photographs most parents now carry on their cell phones have rendered these wallet-sized pictures obsolete. Probably, however, after oohing over the hundredth picture of Little Jimmy on his mother’s 200 gigabyte iPhone, many a person my age must think longingly of the days when adults only had to admire as many photographs as could fit inside a billfold! Fathers tended to be a little less dutiful in maintaining these wallet albums, and the plastic holders would age, becoming yellow and embrittled, ultimately cracking and flaking, so that the pictures beneath were scarcely even visible.

Your school portrait was used in the school yearbook, an annual publication that presented the names and pictures of all the students, teachers, administrators, and other personnel. For students, the most popular part of the yearbook was probably the section of candids, often presented as collages, a montage of the school year, featuring special events (one year Ronald MacDonald visited the school), field trips (usually of an educational nature and often quite boring), school assemblies, and playground snapshots. Playground snapshots invariably depicted the playground as a place of comity and fun.

Everything was the way it always had been, and always would be.

Worksheets were called “dittoes” because they were reproduced on a ditto machine; the text on a ditto was a very pale, lovely mauve that, I think, contained just a touch more blue than straight mauve.

The school principal was always a male, and the teachers were always female, except for the gym teacher who was usually male. The only other male in the school was the janitor. A male grade school teacher was as unthinkable as a male nurse or a male secretary. The all-female teaching faculty and office staff constellated themselves adoringly around their principal. I have sometimes thought that polygamous households or certain cults would be similar to grade schools (and doctors’ offices) in the way the women always seemed to be deferring to their male leader, and competing for his attention and for signs of his favor.

School personnel were all addressed formally, as “Mr. Patterson,” “Miss LaRowe,” “Mrs. Rieker.” Only one teacher went by the title “Ms.”, instead of “Miss” or “Mrs.” Her name was Ms. Menendez. She was younger than most of the teachers, and a far better dresser. She had real moxie too, the way she marched through the hallways with great strides, in knee-high boots and sweeping skirts, giving the impression of very serious purpose. People were obviously bothered, however, by her wish that students address her as “Ms.” We spent much time in gossipy speculation about her. For example, what really was her marital status? Was she married? Single? Divorced? What did she have to hide? Someone solved the mystery by disrespecting her wishes and listing her as “Miss Menendez“ in the school yearbook, but this did nothing to abate the scandal, which was essentially that she had the audacity to flaunt convention. She was an outrage to decency. The younger students processed this outrage by saying she was a witch; the older students said she might be a lesbian, which if true and openly acknowledged would have been a scandal of the greatest possible magnitude, too great even to contemplate, really: it was quite enough, and really almost too much, even to suggest the possibility that she was a lesbian, and you could scarcely wrap your mind around that. A sub-rumor had it that she was “carrying on” with a married man. The two rumors, though obviously in contradiction, were, I think, related: both rumors (along with the G-rated fairy tale version, in which she was a witch) were trying to articulate a feeling that she was an unnatural woman, and a threat to the social order.

Mr. Hepburn, the janitor, was probably the adult in school on friendliest terms with us students. According to one rumor about him, he was in the FBI, which made him seem extra “cool” (not all rumors were unkind, only the vast majority). After grade school, we somehow learned to despise school janitors. Our attitude towards cafeteria workers suffered a similar change. While in grade school, we considered it a privilege to work in the cafeteria, slopping goulash, tater-tots, and canned-fruit-cocktail (in heavy cling syrup) onto white, styrofoam trays. After grade school we began to regard the students who worked in the cafeteria as socially inferior. I think it was generally known, or else believed, that these students had to work in the cafeteria because their parents were too poor to afford the cost of a school lunch. Even in grade school, though, we could be shockingly nasty to adult cafeteria workers, the difference being that we did not despise cafeteria workers as a class, but selectively as individuals, which actually meant that in grade school our hateful genius was expressed with more hurtful creativity, because it did not possess the categorical bluntness of class prejudice.

In the cafeteria, the usual target of our cruelty was Mrs. Beckhart, who was charged with supervising us while we ate. I guess the students despised Mrs. Beckhart for two reasons: first, because she was unprepossessing in the exaggerated ways most likely to capture the attention of children, who seem more likely to notice specific physical flaws and excrescences—a hooked nose, a hairy mole, a lazy eye, a snaggletooth, a foul body odor, an elephantine figure—than to notice bland ugliness in general. The second reason was that, with the cunning of predators, we sensed she was weak. Though charged with the prodigious task of keeping order over 180 students, she was not vested with the power needed to enforce that order. I’m doubted we ever understood the sociological dynamics that rendered her so powerless, but we grasped, at some primal level, that she was tactically outnumbered and out-positioned. In a cafeteria full of restive, loud, mettlesome, intractable children, she had difficulty separating actual culprits from the hoards of rowdy bystanders, and of course a real “cut-up” could set half the lunch table to laughing “hysterically,” which provided cover for the misdeeds of others. One of the few weapons in Mrs. Beckhart’s small arsenal was the power to send students to the principal’s office, but she could not exercise this power without actually catching a student in the act of breaking a rule, and she was not, alas, very skillful at turning witnesses. Obviously she couldn’t send everyone to the principal’s office, or even a whole table. Summoning the principal to the cafeteria, on the other hand, was a course of action used only in extremis, as, I suspect, it would have been tantamount to abdication. So instead she was doomed to waddle from table to table, scolding willy-nilly in a kind of rearguard action. Her other option was to stand in the center of the cafeteria and blow on her whistle, reprimanding everyone, which unfortunately had the reverse effect of making no one feel reprimanded. The second real power available to her was the power of forcing everyone, or at least a whole table, to stay inside during the postprandial recess. We sensed, however, that she could only use this punishment sparingly, perhaps because it interfered with the rest of the cafeteria staff’s ability to clean the multi-use space in time for the gym class following lunch, or else because the school generally frowned upon this measure: without our recess, we would be returned to our real classrooms with all the ungovernable energy we were supposed to have burned off during recess, so that Mrs. Beckhart would have been passing a worsened problem onto the teaching faculty, who occupied a higher status within the school hierarchy: like summoning the principal, this would no doubt have been regarded as a failure to discharge her, after all, fairly modest (on paper at least) set of duties.

We had this bizarre inside joke about Mrs. Beckhart. I never actually understood the joke, but I also never admitted that I didn’t understand. Mrs. Beckhart had very large buttocks, which naturally attracted our malicious attention. Because her job was to supervise us while we ate, she spent much of her time engaged in a kind of whack-a-mole, turning from table to table, leaning over students’ shoulders to scold them, which had the effect of making her large buttocks especially prominent to the children sitting at the table behind her. When this happened, the children confronting her posterior would make a hand-gun shape with their fingers (thumb up; index finger pointed out; middle, ring, and pinkie fingers folded in), point it at her buttocks, fire the gun, and then say “Pow! A fresh loaf of bread.” Whatever this joke meant, it had us all “in stitches” and we couldn't stop laughing.

One of the most impressive achievements in the history of school discipline was convincing us that there existed, for each and every student, a “permanent record,” which supposedly followed you all through life, and very likely into the after-life as well. Students spoke endlessly, and with tremendous anxiety, about the permanent record. Your greatest fear was that your permanent record would be wrecked by some misbehavior, which, if you were caught committing, would go onto your permanent record and be read by every future teacher and even every potential employer, destroying your chances of ever again being treated with impartiality. A blemished permanent record would render you practically ineligible for admission to “a good college.” We even imagined that every future potential employer would have access to this permanent record, and that, when considering your application for employment, would see how in the second grade you had called the substitute teacher “a hag,” and that, after reading about your misconduct, the potential employer would gravely shake his head (all employers were men) and consign your application to the “circular file.” Other types of information that were known to go on the permanent record were your grades and your attendance record. Oddly, I can’t recall any teacher or administrator ever actually mentioning the permanent record, though surely they must have. On the other hand, I can’t help but consider the possibility that this bogey had its origin, or at least its perpetuation, among the students themselves, a Foucauldian example of the disciplinary society at work. Whatever the genesis of the permanent record, most of the dreaded qualities attributed to it, if they ever existed in the first place, had in fact been destroyed by FERPA, which became law the year before I and most of my classmates were born.

The playground was very large, about ten acres. The school had fifteen acres of land. The actual school building was set back 330 feet from the street, with two luxurious acres of immaculately maintained lawn—suitably grand since the district superintendent’s office was housed in our school, a point of pride for us as there were two other, older elementary schools in town (Lincoln and Douglas, the latter named for Illinois’s most famous Copperhead), as well as a middle school and a junior high school. Our school, Jefferson, was the newest building in the district, probably the reason why the superintendent was headquartered there.

Behind the school was a ten acre playground, bordered on the west by a horse pasture; the horses would come to the fence and let you pet them on their muzzles. North of the playground was an abandoned field. Nobody paid much attention to the field until the autumn, when everything in it began to dry out, and then we found much delight in this patch of dead weeds, especially the milkweed. From each milkweed stalk hung pods which, if opened, revealed dollops of silky white strands, source of much tactile pleasure. Attached to each strand, of course, was a seed, and if you blew on these strands they went floating into the air. The brittle milkweed stalks could also be split open, and inside you would find a chewy pith running up the center of the stalk. Somebody told us this pith was Indian gum, because the Indians used it for chewing gum. We would harvest as much of this pith as possible, and store it in our desks, since the teachers did not realize it was actually gum, which was otherwise forbidden in school. Imagination combined with the thrill of the forbidden to lend this basically tasteless substance the faintest flavor of spearmint.

On the northeast side of the playground was a cemetery.

Our school building, which first opened in 1968, was probably a typical example of sixties “school plant construction,” expertly theorized by professional “school planners” to balance the educational needs of “today’s growing child” with the budgetary considerations of the school district, with the latter emphasis centering on built-in adaptability that could accommodate both changes in instructional methods as well as the district’s future growth, a touching bit of ultimately unrealized optimism. The building was probably designed by an expensive, “hot shot” Chicago architecture firm, or perhaps by a less-expensive Peoria firm that specialized in imitating its costlier rivals. The building possessed many of the properties advocated by the more advanced authorities in modern school design: folding tract walls between classrooms, fluidity of space, interior windows, extensible hallways, centrally positioned multi-use common areas with movable partitions, diversified learning spaces, lofted construction with indirect natural lighting, acoustically treated ceilings, single-barreled hallways (school shootings evidently being rare enough to make this last bit of jargon quite unremarkable), “climate control” for student comfort, exposed natural brick walls, carpeted media centers, visible natural landscaping (fabricated nature being more natural, or at least more desirable, than nature itself)—all of it summed up by the buzzwords “flexible” and “organic” design, with flexibility being the answer to almost every modern educational problem, a hilarious irony seeing as actual instruction was probably as inflexible as ever. And even if instruction was not as inflexible as ever, it’s certainly true that the most notable example of this ballyhooed built-in flexibility, the folding tract walls between classrooms, which were to enable “team teaching” and all manner of collaborative, adaptive, and improvisational “learning experiences”—the movable walls between classrooms were almost never used that I can remember. This modern school plant was, apparently, meant to promote the long predicted demise of the “teacher-class,” and to usher in its replacement by an army of educational specialists requiring more fluid, flexible student schedules, none of which really materialized, except, perhaps, in the case of “special education” for “the mentally retarded.” So despite all this built-in capacity for progressive curricula, instruction pretty much remained as traditional as ever. No team teaching, alas; even the movable partitions in the multi-use learning center remained unmoved; no end to the oppressively rigid scheduling or the tyranny of the “self-contained classroom” or the “limited-use library.“ Aside from the building’s abiding ugliness, there was little evidence that the sixties had ever even happened: we still sat in old, lift-lid desks with heavy, steel bases and varnished wood tops, each desk with its original ink well hole. We regarded the ink well hole as some mysterious and frustratingly unusable portal. Boys often put action figures in it, as though Luke Skywalker was rappelling into the depths of the desk.

As a grade schooler I was fascinated by the recreations of girlhood. In first grade, for example, the girls had this playground game where they would claim to know a test a that could conclusively determine whether or not you liked butter. Truly they were like young enchantresses, because by merely claiming to possess this test, they cast a sort of spell over you, and you became instantly convinced of multiple absurdities, the first being that this question—whether or not you liked butter—was of pressing significance, when in reality it was of no significance whatsoever, butter being a kitchen table staple of the least possible interest, except perhaps when spread onto toast and sprinkled liberally with cinnamon and sugar. (Nor do I believe the test was meant to ascertain whether you liked butter as opposed to margarine, because at that age we did not even distinguish between the two.) The second absurdity was that you found yourself believing this test would be a more reliable indicator of your taste than even the evidence of your own senses, as though we hadn't all tasted butter hundreds of times, and didn’t already know whether or not we liked it. The third absurdity, somewhat more implicit I think, was that your taste for butter was in fact a closely guarded secret, and not one that you would willingly have revealed, so that this test presented a kind of challenge to the hesitant: what did you have to hide? Were you afraid this test might actually elicit the truth about you, and about your taste for butter? So they would claim to have this test, and they would ask if you were willing to be tested. If you consented, then they would take a dandelion and rub it on the top of your hand, or sometimes on your cheek or neck. If the dandelion left a yellow mark—and of course it always did—then that meant you liked butter. The rubbing of the dandelion on your skin produced a pleasant, almost erotic sensation, and the entire experience of submitting to this exercise awakened a sybaritic strain in my personality.

Girls seemed to have a special gift for arts and crafts. I remember, in the first grade, being especially impressed by their ability to draw trees. These trees they drew were basically long, brown rectangles attached to large, green circles. I think they might also have drawn smaller, red circles inside the larger, green circle to create apple trees. I was amazed by these displays of skill, and today I’m amazed that I considered something so simple to be so great an achievement. Girls were also masters of the paper folding arts—another one of the mysteries they practiced, like the test for liking butter. If you received a note from a girl, it would be intricately fashioned into a deceptively simple, but perfectly proportioned square, wrapped in upon itself, the folds forming the illusion of a star with no edges: a tantalizing promise of some secret hidden inside, and if a girl gave a boy a note, there always was some secret inside, usually the revelation of an aborning crush (“Do you like Tasha? Yes / No / Maybe. Circle One.”) Of course, there was an elaborate form of diplomacy that accompanied such communications: if a girl handed you one of these artfully folded notes, it was rarely a note from that girl directly to you. Rather, it was a note written by a girl, on behalf of her close friend, to one of your friends, and entrusted to you for safe delivery. So if Tasha liked Ted, then Tasha’s close friend Kim would compose the note, and deliver it to Ted’s friend Eric, who was then tasked with delivering the note, unopened of course, to Ted. Ted would complete the form, perhaps after carrying it around all crumpled in his pocket for half the day, and then return the note through the same channel of intermediaries just described. Suffice it to say, the returned note was never as beautifully folded—usually the boys practiced a simple series of half folds until the sheet was so thick that it could not be folded any further, but the intricate pattern of creases originally pressed into the paper by the note’s creator remained visible beneath the brutishly folded lump of paper, rather like the blossom of a daylily that has been crushed under the wheels of a tractor.

I also envied girls because they got to bring baby dolls to school. Other kinds of dolls like Barbie did not interest me, but I longed for a baby doll, and especially a Cabbage Patch Kid, which, by the second grade, was “the essential toy” for girls. Cabbage Patch Kids quickly became objects of conspicuous consumption—I'm sure there are cultural histories of the phenomenon already written. Coleco, the owner of the Cabbage Patch brand, developed an entire industry around supporting and extending the cult of the Cabbage Patch Kids. The initial allure of the dolls, however, was that they were like real babies. Unlike other dolls, each Cabbage Patch doll was (supposedly) unique, and each came with a birth certificate, stating the baby's date of birth and his or her name. The birth certificate had a secondary function of attesting to the doll’s authenticity as a real Cabbage Patch Kid, not some cheap imitation. There were many imitations, like the Pumpkin Patch Kids—what marketing genius thought any child could be satisfied with such ham-handed fakery?—and woe be to the child whose parents bought her one of these imitations. Only a genuine Cabbage Patch Kid could be like a real baby. Girls even had Cabbage Patch parties, to which each girl would bring her Cabbage Patch Kids. There might have been a variation in which each girl brought only her favorite Cabbage Patch doll, but even in this version you can be sure that the host would still be exhibiting her own collection in its entirety for her guests’ envious delectation, so that these parties were really about creating an opportunity for displaying your collection of Cabbage Patch Kids, since it was logistically impossible to bring more than a couple of them to school, and what other venue existed for showing them off? As I heard these parties described, they were really a forum in which the girls with the most Cabbage Patch Kids could flaunt their superiority, as though owning dozens of these things conferred some exalted status, which of course it did. Needless to say, girls who did not own a real Cabbage Patch Kid either were not invited to the parties, or else were too ashamed to accept their invitations.

I think I was somewhat appalled by the whole idea of these parties, not (regrettably) from some inchoate sense of social justice or even mere human decency. Rather, I was disenchanted by the way in which, at these parties, the Cabbage Patch Kids reverted to the state of mere merchandise, whereas for me the whole appeal of the dolls was that they seemed like real babies. I had no interest in them as collectibles (though I was fully taken in by the allure of authenticity, and definitely wanted a real Cabbage Patch Kid). Oddly, the parties would have been even more grotesque if you restored the nurturing, maternal element to the Cabbage Patch experience, because the parties would then have become vulgar pageants of nubile fertility, in which the girls preened themselves over their abundant offspring. It’s true that each Cabbage Patch Kid was, ostensibly, adopted and none was born of a human mother, but instead plucked from the cabbage patch; and yet the birth certificates were all notarized with official hospital seals, and didn’t the dolls all look the exact same age, and didn’t they resemble each other enough to be biological siblings? So when you heard about these parties, you couldn’t help but imagine the girls as having birthed, dog-like, these inhumanly large litters of babies. All this was, it must be remembered, before the invention of fertility drugs made precisely such large litters of human babies into a reality.

Much of school social life was governed by ritual, and the rituals of girlhood were for whatever reason more visible to me than the rituals of boyhood, perhaps for the simple reason that the outsider is often quicker to recognize the formalities of another group’s social life, even if he lacks the insider’s deeper understanding. One universal ritual of the playground was that you could “report” the misbehavior of children in a grade lower than your own. Actually, you could report a younger student for just about anything, regardless of whether the student was misbehaving. This, in fact non-existent, privilege was exercised primarily as a threat: “I’m going to report you.” The statement meant that the accuser was going to inform a teacher about your misbehavior, but it was really just a way of reminding younger students of their inferior status on the playground.

My family lived behind the county fairgrounds. Every Friday night the county fairgrounds held stock car races, which made the most terrific noise. My brothers and I were constantly begging our parents to take us, but they never did. A married couple, who lived a few houses west of us, had a large backyard that abutted the racetrack, and on Fridays they hosted stock car viewing parties, at which we could sit right in front of the wire fence dividing their yard from the racetrack. The wire fence would have provided zero protection in the event that a stock car ever veered off the track at this point in the course, and very likely we all would have been killed. For my brothers and me—once again obsessing over the difference between the real thing and its imitation—these viewing parties were an unsatisfactory substitute for the imagined thrill of watching the races from the grandstands, no doubt for the simple reason that the latter experience was denied us. I did finally get to attend the stock car races properly, from the grandstands, when a friend held his birthday party there, but I did not enjoy the experience at all, and actually hated it: it was louder, dirtier, and hotter even than the backyard parties had been; the benches were uncomfortable and the crowd far rougher than I liked. The experience would have been better had it remained forever denied, created instead only inside my longing imagination.

Our house was close to the school, and we always walked to and from school. Sometimes we walked home for lunch as well. In my neighborhood were two types of house. On the east/west streets extending west from town (and running parallel to the county fairgrounds) were older, two-story, raised perimeter foundation, wood-frame houses. Almost all of these houses had front porches with porch swings, which I loved and still do. These older homes had obviously been built on large lots, and were generously spaced along the streets. Our house was of this type. Most of these lots had been at least partially subdivided (ours had been subdivided in the back, and possibly to the west as well), and these subdivided lots were mostly filled with smaller, inexpensive, concrete slab foundation ranch-houses. The north/south streets were almost entirely lined with these newer ranch-houses. The older homes were more beautiful, and I liked to imagine what the neighborhood looked like when it was still countryside, and these older houses had the area all to themselves, like a grand fleet of old Spanish galleons traveling high amongst the sea of meadows, for I do not believe any had been farm houses.

Despite this process of infill, most of the older houses retained enough of their original lots to give each a very spacious side yard. Side yards were something I just took for granted: the old houses in my neighborhood had front yards, backyards, and side yards. Some houses had two side yards. The side yards were ideal spaces for playing games like football or baseball, or for flying a kite if the side yard had no trees. One neighbor had a huge, treeless backyard that had never been subdivided, so that it ran all the way from their house to the wire field fence separating their lot from the county fairgrounds. Their backyard was an excellent place to fly a kite. My parents used their own side yard for a vegetable garden, which they shared with the family across the street. As children, we freely trespassed on all the lawns in the neighborhood. There might have been one or two exceptions—people who did not want us on their property and who enforced their wishes. These people had reputations for being scary: usually some oddity, often of a menacing nature, was invented about them, such as owning a gun or a guard dog, or being able to outrun a jackrabbit (and therefore, also, a child). It never occurred to us that people might rightfully not want children running through their property. People never locked our doors, and in the case of our neighbors across the street, my brothers and I would enter and leave their house as though it was our own, and they were really like a second family to us. Later, when I went to middle school and junior high school, I could walk to school entirely through other people’s back yards. I guess it was a pretty kid-friendly neighborhood.

The winters were extremely cold and the summers extremely hot. During the summer my brothers and I usually rode our bikes to the public swimming pool every day. Sometimes during the summer my friend Mike Bassetti and I would pop the tar bubbles that formed on the street in front of his house. He lived one block north of me, in a lovely, blue, two-story Queen Anne with a turret off the master bedroom. Because all the houses between his and mine were ranch-houses, I could see his house from my bedroom window. His sisters had the bedroom facing south (mine faced north), and my brothers and I would sometimes try (unsuccessfully) to spy on the sisters using a telescope we got one year for Christmas.

As my classmates and I progressed through elementary school, our knowledge of history and of the world obviously began to increase, but typically in ways that prove the saying “a little knowledge is a dangerous thing.” Too often we found our knowledge inadequate to the task of explaining our actual experiences. In these cases, we fashioned history and reality on an ad hoc basis, using a technique best likened to bricolage or pastiche, taking scraps of information learned at school and at home and through observation, and then gluing it all together with a compound of emotions. For example, much mystery surrounded one of our classmates who was always removed from the classroom whenever we celebrated birthdays, or other holidays like Halloween, Christmas, and Valentine’s Day. These celebrations were among the most fun events of the entire school year, and sometimes occupied as much as half the day. I wondered where he went—did he sit alone in a room knowing that everyone else in the school was having fun? Naturally we wondered why he was not allowed to participate. A consensus emerged that he was a Jew. Probably, apart from Christians, Jews were the only other religious group we knew of. Most of us would have learned about Jewish people in Sunday School, and many of us would have known something about the persecution of Jews during World War II. We must have learned something about the Holocaust in either third or fourth grade, because around that time a girl in our class darkly explained to us that, if the Russians were to invade—and a Russian invasion remained a source of fear during the early eighties—then this boy and his family would be sent to concentration camps. I don’t know how she reached this conclusion, but I remember everybody accepting it without question. Perhaps, instead of bricolage, reality was construed through a complex game of telephone, with multiple, simultaneous transmissions being mixed and distorted in the process of retelling, and then further distorted in the ultimate synthesis: somebody’s parent must have (correctly) said that this boy was Jehovah’s Witness. Perhaps somebody else's parent said that Jehovah’s Witnesses were sent to concentration camps during World War II. A lot of kids would have known about the concentration camps primarily as a place where Jews were sent. Further distorting the message was a misunderstanding of World War II: I think many of us believed that the United States fought the Russians in the Second World War, not the Germans. I’ve often wondered how I could have conceived so mistaken an idea. My babysitter’s husband had served in Europe during World War II, but most of his service abroad was performed after the cessation of hostilities. The stories he told my brothers and me were of patrolling the frontier in the American Zone of Occupation. In these stories, it was always Russians, not Germans, whose presence was regarded as a threat. Perhaps I concluded that World War II had been fought against Russia, and this squared with what little I already knew about the world: the enemy was Russia, and remained so, all of which would have, in my mind at least, our informer’s statement.

I was born five days before the Fall of Saigon, a fact I only learned as an adult. I grew up believing the Vietnam War was something from the distant past. People didn’t talk about Vietnam, though there must have been veterans in our town, and families who had lost sons. Surely at least one of my classmates had a father who fought. And yet you were far more likely to meet a veteran of the Second World War, and certainly more likely to hear people talk about it. The Vietnam War just seemed to have been erased from polite conversation. The veterans, if there were any in my childhood, were invisible, or at least the fact of their service in Vietnam was invisible. Looking back, I find this occlusion to be especially eerie since one of my classmates was a girl who had been adopted from Vietnam as an infant, by a white family in our town. The kids at school didn’t really think of her as Vietnamese, or even as Asian, though. All the kids thought she was black. There were no black students in our grade school. This girl was treated very badly, I've no doubt due to racism, and yet race was not an obvious predictor of mistreatment. There were other non-white students in our school, students who were not, to my knowledge, mistreated because of their race, certainly not to the extent that this Vietnamese girl was. Two students in my school were Latino, and one was among the most popular kids in the entire town. Ms. Menendez, whom I have already written about above, was Latina, and yet I never remember anyone remarking upon her race—people were far more bothered by her wish to be addressed as Ms.

My sexual education informally began in grade school. We first learned about sex on the playground, from our friends, sometime during the third grade. By the fourth grade it was common for boys and girls “to go out,” which did not imply going on dates, but did denote a heterosexual relationship, without actual sex. These relationships were similar to playing house, where we acted out our roles as though we were actually involved romantically, but relying heavily on our imaginations to supply what reality could not. Still, there was actually a physical dimension to these relationships, but severely limited. For example, we might hold hands at the movies, or on a ”Moonlight Couples Only” skate at Skate-o-Rama. A ”Moonlight” skate was a love song played over dimmed lights, with the disco ball sending spots of soft-white light spinning around the rink. If you were going out with a girl, then it was expected that you would skate with her during a ”Moonlight” skate, and that you would hold hands. However physical we actually became, I have no doubt that, in our minds at least, the sex component was ”full-blown.” Madonna’s record Like a Virgin was released the fall of my fourth grade year, and I really don’t think it’s possible to overstate this record’s significance, or the significance of Madonna, for children my age. Over the course of my fourth grade year, four hit singles were lifted from the album, each one a sex hook in our heads, “on heavy rotation,” until all our little minds were blissfully slashed into a euphoric sex slush. Madonna made us all sex-crazy, and this possibly explains the importance of “going out” with girls at such an early age, and why we took these relationships so seriously. In hindsight, of course, the relationships seem silly, since obviously there could be no real sexual relationship, but Madonna had us all rushing to heterosexuality, like kids ”cannonballing” into the swimming pool at the end of rest period.

So I definitely thought of myself as being attracted to girls, but I was also aware that, for me at least, part of the pleasure of ”going out” was that it involved considerable bonding with my male friends. Your male friends assisted you in the courtship, just as the girls’ female friends assisted them, as I have described above. Furthermore, these romantic relationships became subjects of conversation between friends. It was typical, not unlike adult relationships, to discuss your romantic intentions with your male friends before even revealing them to the object of these intentions, whether that was asking a girl to go out, or announcing your wish to break up. Furthermore, it was common to spend more time discussing your girlfriend with your male friends than you actually spent in the company of the girl herself, so that these romantic relationships existed most fully, and most vividly, through conversation with your male friends. These conversations were vehicles of intimacy that resist my attempts at explication: if you admit that your relationship with your girlfriend is, at least in theory, a relationship of intimacy, then sharing details of that relationship with your male friends also becomes a form of intimacy. Later in life, when I finally accepted that I was gay, I felt guilty for having, in a way, practiced a deception upon all the males who had been my friends. The homosexual was, as Auden expertly evoked in his figure of the spy, “Expert impersonator and linguist, proud of his power / To hoodwink sentries,” though often unsuccessful at it: “He, the trained spy, had walked into the trap / For a bogus guide, seduced with the old tricks,” but still “Sap unbaffled rises,” and he continues to hope, naively: “Do you think that because you have heard that on Christmas Eve / In a quiet sector they walked about on the skyline, / Exchanged cigarettes, both learning the words for ‘I love you’ / In either language, / You can stroll across for a smoke and a chat any evening? / Try it and see,” always an exile in strange places, “The land, cut off, will not communicate,” doomed by his very isolation, “They ignored his wires. / The bridges were unbuilt and trouble coming,” who usually ends up shot, “The agent clutching his side collapsed at our feet, / ‘Sorry! They got me!‘,” killed for a moral crime he never even got to commit: “They would shoot of course, / Parting easily who were never joined.”

These confusing feelings began for me in the fourth grade. I understood—with that pale, hazy unclarity in which children often apprehend truths either unbidden or forbidden—I understood that I was attracted to other boys, possibly even more attracted to other boys than to girls. This was also the time that AIDS came crashing into our isolated little world, and I remember learning about AIDS in the fourth grade, and by “in the fourth grade” I mean in school, in class, from the teacher; and this was exactly the same time that I learned—in school, in class, from the teacher—about homosexuality: I learned about homosexuality through learning about AIDS, the one inextricably linked to the other, because AIDS was initially a disease of homosexuals, and subsequently a plague wrought upon the nation by homosexuals. To whatever extent homosexuality would, in any case, have been regarded in my town as immoral or perverse, AIDS turned it into an abomination for which there was, quite possibly, no precedent, for now there was a genuine public health crisis yoked to this perversion of nature, and the first images of real homosexuals that confronted my ten year-old mind were ghastly images of hideously ill men dying horrible deaths, deaths these men were dying because they were homosexuals. The male homosexual was an object not only of condemnation, but of fear, and this fear became hysteria: a public health crisis that was also a moral crisis. That’s how I first learned about my own same-sex desire, and how I first came consciously to understand myself as afflicted with homosexuality, and to understand that it must remain a carefully guarded secret, especially since people seemed already to be guessing the truth: I heard the words “faggot” and “fairy”—people were “on to me,” and I began trying to practice concealment, misdirection, and deflection: I lashed back out, however unconvincingly, by calling other kids “faggot” and “fag” and “fairy” and “homo.“ Hadn’t I learned in kindergarten that survival was largely a matter of disposition? So deception would be the new disposition. I never wanted to be gay, and if I could have chosen I would have, without hesitation, chosen not to be gay, and perhaps would still do so.

There were two other public elementary schools in our town, as well as a Roman Catholic parochial school. We came to know about the existence of students at these other schools through encounters outside of school. The nature of these encounters depended largely on the context. In so small a town, you were likely to meet students from other schools at places like the roller skating rink, the movie theater, or the public swimming pool. These encounters tended to possess somewhat the character of gang confrontations: the kids would cluster into groups of other kids from their own schools, and a harmless skirmish might ensue—mostly a matter of posturing and the exchange of tough words. At the very least these encounters filled us with the thrilling expectation that such a skirmish might materialize. I don’t recall any real violence, however. You would also meet kids from other schools through organized activities like Little League (baseball) or Park District (summer day-camps). Organized encounters tended to be more civil, and might even result in friendships, especially where a team sport like baseball was involved, because the juvenile instinct to form gangs was channeled into your team, and overrode school loyalties, which in any case would be almost dormant since Little League was a summer activity, and with school not in session summer always felt like a liminal state, during which the conventions of school did not necessarily obtain, and almost anything might happen. “Park District” was what we called summer camp. We had no concept of it as an administrative arm of the city. It was simply the name for the panoply of summer activities that were, in fact, organized by the Park District.

The other main venue for meeting students from the other schools was Sunday school. It was taken for granted that all your classmates were Christian, and almost all of them were at least nominally affiliated with one of the churches in town. My brothers and I were sent to Sunday School at the First United Methodist Church. As a family, however, we had little sense of religious identity. We did not talk about God or Jesus or Christianity at home; I’m not even sure if we owned a Bible—if we did, then I never saw it. Nor did I know what it meant to be a Methodist, as opposed to being a member of any other Protestant church, although I question weather my friends from more religious families did either. I had a more nuanced understanding of the different church league softball teams than I did of the doctrinal differences between those churches. Our town had over twenty churches:

- Bethel Baptist

- Bureau Township Missionary

- Christian Science

- Church of Christ

- Church of the Nazarene

- Congregational Bible (Wyanet)

- Evangelical Covenant

- First Baptist

- First Christian

- First Lutheran

- First United Methodist

- First United Presbyterian

- Gospel Tabernacle

- Hampshire Colony Congregational

- Jehovah's Witnesses

- Kasbeer Community

- Princeton Bible

- Seventh Day Adventist

- St. Christopher’s Episcopal

- St. John Evangelical Lutheran

- St. Louis Roman Catholic

- St. Matthew’s Lutheran

- United Pentecostal

- Wesleyan

- Willow Springs Mennonite (Tiskilwa)

Although my brothers and I attended Sunday School regularly, we attended church only two or three times a year (Christmas Eve, Easter morning, and then maybe one or two other times), and those were also the times that my parents attended church.

My brothers and I learned at a fairly early age that, although the question of which church we attended was of little consequence to us personally (nevermind spiritually), since we didn’t even understand the differences between them, it was of considerable consequence to my father’s relatives, who were all “seriously” Roman Catholic. My paternal grandmother knew that my parents were not raising my brothers and me in the Roman Catholic church, but this information remained a carefully guarded secret from the rest of my father’s family, who all lived thirty miles away. His side of the family already regarded my mother as a bit too modern, a fast East Coast girl with some troublingly progressive notions about wifehood and motherhood. My mother would not, for example, allow our grandmother to “take the switch” to my brothers and me when we misbehaved. My father’s relatives, especially the great aunts, likely suspected that my mother was insufficiently deferential to him, even though she fulfilled the traditional wifely duties like cooking the meals and doing the laundry, in addition to working her own full-time job. My father had been a star athlete in their small town, and was the pride of the family. The great aunts no doubt considered it something in the way of a tragedy that he should have been captured in marriage by such a woman as my mother, whom they probably regarded as something of an adventuress, which is a little comical since my father’s family had no great fortune, and were actually quite poor. I think, however, they valued athleticism far more than any other form of worldly success, so that my mother was even worse than a mere fortune hunter! As if to make matters worse, my parents’ marriage was practically an elopement, held in the Iowa town where they attended college, with little or no family attending.

The great aunts probably wondered what the world was coming to, and well they might: they were mostly spinsters or widows, living in the old family home, a place my brothers and I all found as suffocating and creepy as a funeral parlor, not just because of the eternally drawn drapes, or the electric organ in the living room, the shrine to the Pope, or the religious bric-a-brac spread about the home as densely as merchandise at a diocesan gift shop—what we hated the most were the physical expressions of affection that the great aunts extracted from us, though we scarcely knew them. They were always saying, “Come give your aunt a kiss,” and it was the kind of unwelcome kissing and hugging to which you might submit as a grudging form of emotional tribute paid a grieving widow, inconsolable and prostrate with unleashed emotion, at her husband’s wake. But we felt compelled to kiss these women as a matter of routine, and to let them kiss us—sometimes on the lips, which we didn’t even do with our own parents. This kissing was all the more funereal because the great aunts covered their faces and lips in thick thick layers of make-up, which combined with poor circulation to make their flesh feel cold, like the flesh of a corpse.

My mother’s side of the family had a similarly conflicted religious history. Like my mother, my maternal grandmother also married a Roman Catholic, and also refused to convert. My maternal grandmother was raised by her Jewish father. He had married a Protestant, who either refused to convert or else was never invited to do so—whatever the case, she became estranged from her family, and eventually remarried, beginning a new family to replace the one she left behind. My maternal grandmother, therefore, was raised as a Protestant Christian by her Jewish father and her Jewish aunt. My mother was devoted to this grandfather, and to the great aunt as well. When her grandfather died, she inherited his large book collection, and so growing up we always had interesting books in the house, as my great grandfather had been an avid reader. My mother read many books to us, both children's books and adult books. The latter she mostly selected from the library she had inherited from her grandfather—I know this because the books were old, and they were all marked with his return address label on the upper right corner of the front paste-down. Although I never thought it strange at the time, I am surprised now to think about some of the adult books she read to us, books by authors like Orson Welles, Oscar Wilde, John Steinbeck, Ernest Hemingway, and Edith Wharton. I am grateful to have grown up in a house with many books. One of the books she read to us was Ethan Frome, and I remember assuming she must have identified with the character of Mattie, because that character was from Stamford, Connecticut, which was also my mother’s hometown. Recently I reread Ethan Frome, and have again wondered about the way in which my mother might have identified with the character Mattie, because not only is Mattie from Stamford, but the book is, in part, about her being exiled to a thinly populated, isolated town. Wharton devastatingly thematizes isolation, as well as silence. I can think of few other novels that so painfully evoke the desperate feeling of isolation, and of being crushed by silence.

When fourth grade ended, I went to a new school, Washington Middle School, where the fourth graders from all the town’s grade schools finally became part of a single class, all the kids you had met in Sunday school and in Little League and at the swimming pool and at the roller skating rink and in Park District—we all finally came together and became the fifth grade.

Whatever else there was, well, silence has long since covered it like a gentle snowfall blanketing a field that has been worked hard all summer and fall, erasing a hard-used reality beneath, or at least seemig to do so.