The 1975 Live in Chicago: An Outsider's Report

The 1975 are currently touring the United States in support of their excellent new album, A Brief Inquiry into Online Relationships. The band's frontman, Matt Healy, has been both praised and ridiculed as a kind of postmodern troubadour, in the most reductive sense of the word "postmodern": glibly self-aware, self-referential, ironic, and dismissive of the past. The new album addresses this perception (or misperception?), in part by giving a very un-postmodern treatment to themes like truth, authenticity, reality, and sincerity. In an interview with Billboard, Healy has said, But I know that you know that I know that this isn't real [...] It's difficult because everything's so postmodern and self-referential and hyperaware of everything being bullshit. As I grow as an artist, I just want to be sincere

.1 The band's live shows take this reckoning one step further: they perform in the grand manner, drenching their concerts in imperial pop nostalgia, though many fans won't recognize it. In these live performances, Healy proves himself a master of the tradition in which he works, and makes achingly clearly that if he ever seemed dismissive of the past, it was only because he was questioning the possibility of a past, a past for which he increasingly seems to yearn.

The pop concert, of course, is part of a much older tradition, the tradition of traveling entertainment, which includes vaudeville, circus, carnivals, Chautauqua, the lyceum, barnstorming, touring Broadway shows, traveling exhibits, menageries, orchestral tours, all manner of road shows, tent revivals, and freak shows.

A 1975 concert is most similar to the tent revival, and Healy possesses the vatic quality of a revivalist, with his ability to spellbind his audience. The success of both a tent revival and a pop concert depend upon the audience buying into the idea that what they are witnessing is nothing less than the performer in an inspired state: His flashing eyes, his floating hair! / Weave a circle round him thrice, / And close your eyes with holy dread / For he on honey-dew hath fed, / And drunk the milk of Paradise

.2 The revivalist must make his audience believe that he is really and truly filled with the holy spirit, and this belief enables the speaking in tongues, the holy rolling, the snake handling, the miraculous cures, the cleansing of sin. The revivalist uses the power of his personality to express and project grace. Contrasting the revivalist with the priest is instructive: the personality of a priest is irrelevant; he vouchsafes grace through the formulaic administration of sacraments, a power conferred upon him by ordination. Sacraments administered by charismatic priests and uncharismatic priests are equally efficacious. For the revivalist, however, personality is everything. The priest is a technician, the revivalist an artist.

What is true for the tent revival is basically also true of a 1975 show: Healy must, through the power of his personality, convince us that we are witnessing an authentic expression of his genius, and it's important to note that, contrary to recent usage, the word "genius" refers not to extraordinary intellectual aptitude, but to a numinous quality, to divinity and spirit. How else can we explain the states of ecstasy that overcome his fans? They are seized by an almost Dionysian frenzy, offering themselves up bodily, for Healy's sexual enjoyment. At a 1975 show, you hear young women and young men screaming "Fuck me Matty!" For his fans, Healy is god-like, and I suppose it can only be regarded as a privilege, a sign of election and grace, to be chosen for this sacrificial role, to be consumed by the godhead (forgive the unintended pun). There exist, of course, so many cultural antecedents for this phenomenon, stretching back to ancient history, that to enumerate them would be pointless, even if I could.

Obviously, what I'm describing here is true not just for Healy, but for many pop stars. Even a mediocre singer can attract a fervent following if he possesses that impossible-to-define quality that often travels under the name of "charisma". The cult of the pop star, therefore, depends as much on the personality of the artist as it does on the quality of his art, and many have argued that this archetype emerged from the cauldron of European Romanticism, that it went to ground with the ascendancy of Realism, Naturalism, and finally the lifeless formalism of the Modernists, only to become resurgent in the 1950s with the popularity of Beat writers like Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Burroughs. This archetype is the artist as inspired, but tormented, genius. The pop star's self immolation through drug abuse became an updated version of the suffering poet doomed to die young, and Healy seems to embody the type, even as he tries to distance himself from it. In 2018, Healy spent two months in rehab, recovering from heroin addiction. When interviewed, he now insists he does not want to romanticize his struggles with heroin, but in his own accounts of those struggles one recognizes the figure of the rock star who almost self medicated himself to death. When Chatterton committed suicide in 1770, he cast the mould for a new kind of celebrity artist, whose tortured genius is a forge that forever binds his personality to his work. It's not at all unusual for the personality of an artist to eclipse the artist's actual work: most people have heard of Byron and Shelley, but few people actually read their poems.

This mythopoesis helps explain the peculiar business model of contemporary pop music: never before has musical performance been so closely tied to the individual who purportedly wrote the music (or who first recorded it). Even within the tradition of pop music, this fusion of performer and song has been a fairly recent development, certainly not dominant in the earliest years, when pop stars often did not write their own music, and popular songs were commonly recorded by many different acts. (See Appendix A for an incomplete list of songs recorded by multiple artists.) This practice was especially common in the 1950s, and continued into the sixties, after which the it began to dwindle, so that one particular recording increasingly became canonical, and the idea of anyone else performing the song, except as a cover, often in the form of a tribute, is today almost unthinkable. Try to imagine, for example, Taylor Swift recording "Love It if We Made It", and then issuing it as a hit single. And yet Janis Joplin is the performer most closely associated with "Me and Bobby McGee", even though that song was actually written by Kris Kristofferson, who released his own recording of it in 1971, the same year as Joplin's. "Me and Bobby McGee" was a posthumous hit for Joplin, who had died the previous year of a heroin overdose. Jerry Lee Lewis also released a recording of the song in 1971, and also had a hit with it. Despite the fact that at least three different artists released recordings of "Me and Bobby McGee" in 1971, including the person who actually wrote it, the song is not uncommonly credited to Joplin. It even appears on tribute albums to her.

Tributes aside, covers are generally held in low regard by the music business, probably because the industry is so heavily invested in its stars, perhaps even as much as it is invested in music, and the record labels have an interest in protecting and cultivating the fragile mystique of those stars. The frequently mocked cover band is the result of this extraordinary development. The whole concept of a cover band would be unthinkable in any other musical field. Is, for example, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra a cover band, since they don't write the music they perform? Cover bands are widely regarded as a joke in a way that no other amateur musical ensemble would be. The problem most fans have with cover bands is that cover bands are not the real thing; the cover band's music is a forgery, usually a cheap forgery at that.

---

Is that designer?

Is that on fire?

Am I a liar?

[...]

When you bleed, say so we know.

Being young in the city,

Belief and saying something.

Gone off designer,

It's all on fire,

And we're all liars.

--"I Like America and America Likes Me"

---

Traveling entertainment in American culture is discursively freighted with anxiety over fraudulence and authenticity and exploitation. In American culture, this anxiety is coupled with a deep ambivalence, rooted in the desire to believe: the evidence of your eyes (spectacle) in conflict with the evidence of your mind (reason). Americans, perhaps all humans, seem simultaneously attracted to, and revolted by, the horrible. Perhaps more than any other traveling entertainment, the freak show embodies this ambivalence, and one of the great works of American literature, "Keela the Outcast Indian Maiden", uses the traveling freak show for its potent signifying power. The story is about a crippled black man, named Lee Roy, who is abducted and put into a traveling freak show. His abductors paint his face red, and dress him like an Indian girl, and make him eat live chickens: he bites the head off a chicken and drinks the blood that gushes from its neck, before consuming the chicken while its heart still beats. The performance is real—Lee Roy really does eat the live chickens—but is also fraudulent, for Lee Roy is neither a girl nor an Indian. Another character, a white man named Steve, who joins the traveling freak show as a ticket salesman, becomes wracked with guilt when he learns that the show is a fraud, and that Lee Roy isn't really a savage Indian maiden, but a crippled black man who had been abducted. He repeatedly insists, to anyone who will listen, that he had truly believed the performance was real. The story is, of course, about race in America, but the author uses traveling entertainments to thematize our fragile purchase on reality.

---

And you're a liar,

At least all of your friends are,

And so am I.

---"You"

---

As part of their current tour, the 1975 played a show at the United Center in Chicago on May 8th. When the band's U.S. tour was announced last year, I agreed to attend the Chicago performance with a friend, who is a janissary of the band (on the previous tour she followed them all across the Midwest). Since she and I would be traveling to Chicago from different directions, I decided to make my journey by train. (See Appendix B for details on my trip.)

I have known this friend, Diana, since I was four or five, and she sometimes babysat for my brothers and me. She first introduced us to pop music through Madonna and Culture Club. I wouldn't even have known about the 1975—my taste in music is frozen at about the year 2001—had she not taken me to see them three years earlier in Champaign, where I live. As long as I've known her, which is almost my entire life, she has had a keen taste in pop music, and over the years she's developed an encyclopedic knowledge of it, so that attending a concert with her is always a fascinating experience.

Diana has some reservations about the newest album, and says The first EP is perhaps some of their best work, followed by the debut LP, The 1975, when I first became infatuated with their fresh new original sound. But their masterpiece is I Love It When You Sleep..., which is stunning, amazing, and one if my favorite records of all time, right Up there with Queen's A Night at the Opera and Tears for Fears' The Seeds of Love. It's classic but so modern. So, A Brief Inquiry... was a hard follow up and, Matt Healy was in rehab for much of its gestation period. It has some good moments...but it's overthought and they turned all futuristic on their original beautiful sound and drained the hell out of it. 'I'd Love It ( If We Made It)' is the only moment that comes close to the last two records and maybe even their first EP, with 'Antichrist', 'Undo', and some of their most amazing songs. But good news: they have another album dropping in 2020 that Matt says is much better and more of a story like the last album.

Our friend Ethan dislikes the band, and says The singer is a wannabe Michael Hutchence, with the vocal range of an AutoTune. Their songs are trite and bland, and he has the charisma of an old broom.

Diana answers, Critics such as Ethan, and I say this with affection, are portrayed in the band's video 'The Sound'. I love the 1975! Not so much angry boys, but you cannot put them in a box. They are heavily influence by the music that I love and that we all grew up with. Think back to the era before rap, when danceable pop rock of the MTV generation was supreme. You can hear their heavy influences from Michael Jackson, Fleetwood Mac, Scritti Politti, pop fun that shamelessly just sounds great and makes you want to dance. Lots of pop, alt, house fusion breakdowns, soulful and romantic acoustics!

I took an Uber from my hotel to the United Center. I love riding in a car through the city at night, especially a warm night when I can have the car window open. Chicago, like many cities, is at its most beautiful in the nighttime. "The City" is the name of the second track off the 1975's debut long player. The video for the song seems to suggest that the city is a place to find sex and, ultimately, violence and death.

The journey is a recurring metaphor in articles about the 1975, especially in reference to the band's long history together: they formed while still in school—Healy was only thirteen—and they worked ten long years before finding a record label to release their eponymous debut. The journey metaphor also appears frequently in articles about Healy's recovery from heroin addiction. A concert tour is, on the other hand, an actual journey, and a useful reminder that the figurative is sometimes more painful than the literal.

Arriving at the United Center, I saw lots of police in bullet proof vests carrying machine guns, and also several K-9 units. The United Center is where the Democratic Party held its National Convention in 1996, nominating Bill Clinton a second time to be their candidate for President of the United States. This 1996 convention was widely viewed as a do-over for the city, after the disastrous 1968 Democratic National Convention, which was held at the International Ampitheatre, a now-demolished arena that had been built on a lot next to the Union Stockyards. The presence of police in SWAT gear brought to mind the civil unrest at the 1968 Convention. I wondered what other concert attendees would make of this visible police presence. Many of my friends and acquaintances, especially those much younger than I (yes, I mean those much maligned millennials among whom the 1975 is especially popular)—many of these people hate the police. I mean "hate" in the sense that I have heard them say "I hate the police". I do not know in what sense they are using the word.

As I approached and then entered the arena, I saw the crowds of young fans, and I understood that I was, at the very least, a stranger or outsider, and possibly even a kind of spy who had managed to slip through a frontier crossing into a foreign land.

---

The 1975's current album, A Brief Inquiry into Online Relationships, like its predecessor, debuted at number one on the rock charts.

---

Arena concerts are a curious thing, and surely a challenging venue for bands. First of all, most arenas are not really designed for concerts, but for athletic exhibitions, two largely antithetical cultures. At an arena, the entire show must be superimposed over whatever professional or college sports team more regularly makes its home there—the United Center is all about the Chicago Bulls and Chicago Blackhawks, and everywhere you look inside the United Center you see banners and signs and posters promoting team spirit. I find this aesthetic disjunction a little annoying, but it might not be an issue for the younger generations, since they seem almost constantly to be looking into their phones—even while walking, even while in groups, even while walking in groups—so perhaps they create their own environments with their phones, and carry those created environments with them everywhere they go. In the bathroom, one guy was Bluetoothing 1975 songs to speakers he wore on his belt.

---

Arenas account for more than 75% of all rock concert revenue.

---

The United Center is the largest arena in the United States in square footage, but is only the third largest arena in seating capacity.

---

I had previously attended five arena concerts: Whitney Huston in Peoria, on July 24, 1987; Smashing Pumpkins in Normal, on March 23, 1994; Marilyn Manson in Madison, Wisconsin, on April 24, 1999—just days after the Columbine massacre, for which he was held to be indirectly responsible; Interpol in Champaign, on September 24, 2005; and the 1975 in Champaign on October 28, 2016. Now I would be seeing the 1975 for a second time, though in an arena almost 45% larger.

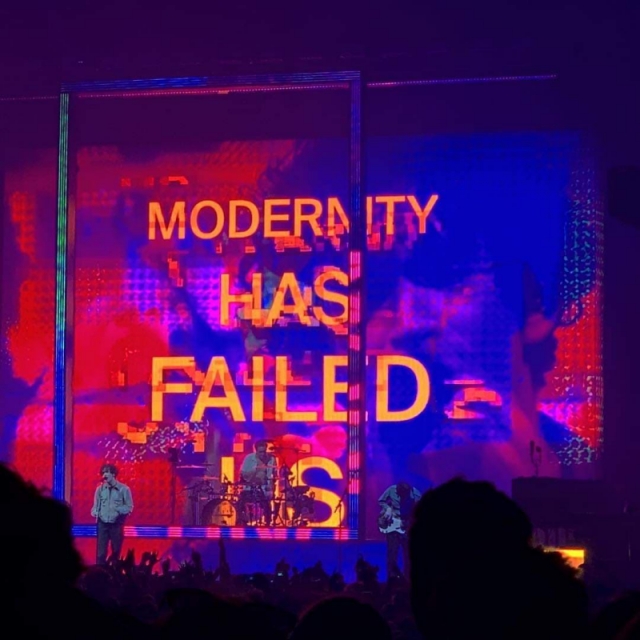

The current 1975 show was designed by Tobias G. Rylander. The visual centerpiece of the stage show is a dazzling array of gigantic LED video contraptions that flash words, images, color, and sometimes transform themselves into a receding tunnel. Rylander says he wanted to convey the weight of technology vis-à-vis social media, screen time and surveillance; the constant pressure of being on camera or onscreen

.3

It's impossible even to imagine the number problems Rylander must have had to solve in designing this show, not least of which is the problem of making the show scalable to every sized arena on the tour. How, for example, do you make spectators at the farthest reaches from the stage feel part of the whole experience, without simply projecting the performance onto giant screens? I thought Rylander handled the problem admirably: there were enormous screens to be sure, but in addition to projecting close-ups of the performance, the screens intermittently displayed slogans and images and dazzling displays of color, so that the screens were part of the show even for spectators standing closest to the stage. Healy himself interacted with what he saw on the screen (even if it was only to admire his own image displayed there, much like Instagram enthusiasts captivated by their own selfies), which further served to make a virtue of necessity. So the solution really did solve the problem of providing spectators in the arena's periphery with an immersive experience similar to that enjoyed by those nearer the center. At the 2016 show, also designed by Rylander, I was able to view the performance from different positions in the arena (because the show was far from sold out), and I have to say that the view from a distance was, in many respects, superior to the close perspective. The distant view felt cleaner, more cinematic, with greater ranges of dramatic effect. The disco-pop-fantasyland Rylander created for that 2016 tour actually won an award.

The element I found least effective was the moving walkway, like the kind you see at airports. Healy used this device to simulate walking in place.

Two studio hip-hop dancers contributed greatly to the stage show.

On this night I was reminded that for sheer spectacle, nothing can rival the experience of seeing a really big act, with their legions of fan-girls and fan-boys, and their big, extravagant stage show and impossibly gorgeous sound system—speakers the size of houses, with more technology than an M16 fighter jet, that can make anything sound fan-fucking-tastic alongside all the rest of the visual deluxity created by Rylander. And part of the spectacle of course are the crowds that must be seen to be believed.

I'm 44 years old, and it's very likely that, of the several thousand attendees, my friend and I were by far the oldest. This band is not of my generation, and its fans are not of my generation, and their songs are about their own generation, and for their own generation. I would put the average age of attendees at about 20, maybe 21. At my age, you feel like a bit of an interloper at such a concert, because pop concerts are always a special experience between the artists and their fans, an almost religious experience, as described above. In the case of the 1975, both artists and fans share the quality of youth, from which I am excluded. My friends and I are out of place, a bit like voyeurs if truth be told, though we didn't want to be. I kept noticing these groups of young people leaning languorously against the hallway walls, staring dreamily into their phones, each person eerily glowing with an almost post-coital mien, as if "propt on beds of amaranth and moly, / How sweet (while warm airs lull us, blowing lowly) / With half-dropt eyelid still, / Beneath a heaven dark and holy".4 Yes, there is something unsettling about seeing people in such a state of languid contentment. Unlike the voyeur, who watches in secret, however, we were quite conspicuous. And yet, strangely, I did not feel conspicuous or even noticed. Between their cell phones and the fabulous stage show, the fans had little remaining attention capacity to waste on us. Nevertheless, I was acutely aware of myself as an outsider, a trespasser, a stranger.

---

I tell you lies,

But it's only sometimes.

---"TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME"

---

The other concert-goers seemed wrapped up in their own adventures, which is to say wrapped up in whatever was happening on their cell phones. They apparently cannot enjoy the concert as much as they can enjoy the image of themselves enjoying the concert: Even your animalism, you want it in your head. You don't want to be an animal, you want to observe your own animal functions, to get a mental thrill out of them. It is all purely secondary and more decadent than all the most hide-bound intellectualism. What is it but the worst and last form of intellectualism, this love of yours for passion and the animal instincts? Passions and instincts you want them hard enough, but through your head, in your consciousness. It all takes place in your head, under that skull of yours. Only you won't be conscious of what it actually is: you want the lie that will match the rest of your furniture

.5

The opening band, Pale Waves, seemed manufactured and meretricious. They performed a couple good pop songs, but mostly sounded like imitation 1975, with female vocalist instead of male. I think it was while watching this opening band that I realized how much stage presence a band needs to command an entire arena. Healy's stage presence has sometimes been ridiculed as "preening" and "self regarding", but you have to wonder whether those qualities aren't perhaps elicited by the demands of an arena venue. "Stage presence" is a dramaturgical expression of fairly recent coinage—the Oxford English Dictionary dates it at 1929, and defines it as the (forceful) impression made by a performer on an audience

—a somewhat odd definition since, presumably, all impressions imply the use of force, which is what leaves the lasting trace (think of a screwpress—the force of the screw applied to the platen is what causes the type to leave its impression on the paper).

Healy clearly grasps the importance of projecting images of himself, and of keeping those images fresh. Before announcing their second LP, Healy told fans to expect a change to the band's "projected identity", and the Rylander-designed stage show is itself a machine for generating and projecting those images. Sometimes, while onstage, Healy stops and stares at the projected image of himself, which is to say he stares at the image of himself staring at the image of himself, a perfectly meta moment, and perhaps an indication of just how well he understands that a pop show is at least as much about the pop star himself as it is about the music.

Whatever creates stage presence, Pale Waves most definitely did not have it. The lead singer wore a short plaid skirt, which was either an homage to the great women indie rockers of 90s (I'm actually not knowledgeable enough to delineate the genealogy of the plaid skirt's appropriation by female rock musicians), or else it was a shameless rip-off. Whatever her intention, it seemed pretty doubtful to me that many in the audience would make the connection to rock music history, and it's unfortunate because these earlier female rockers took this quintessential symbol of gender difference and gender inequality, and they turned it into a big "fuck you". But then Britney Spears came along, and made it all about the nubile female body again. Pale Waves seemed to be leaning more towards the former, and yet it felt so formulaic—as if they had all visited the mall before the show, and purchased their outfits from Hot Topic. Once you've joined yourself to a multi-million dollar concert tour, the authentically subversive look becomes difficult to obtain, and it's more effectively done by somebody like Madonna, who just makes everything bigger and more transgressive. Courtney Love did something similar, lunging across the stage in a tiny satin nightgown with no underwear. The plaid skirt is too slight a symbol to make much impact on a crowd of 20,000 people. The audience must be convinced that you're the real thing.

---

And don't call it a spade if it isn't a spade.

---"The City"

---

Healy tells the crowd that he had his worst hangover ever in Chicago, but is this just the obligatory attempt to connect with the local audience, his version of hailing the city where the band is performing (which he also did repeatedly) as a way to establish rapport, a way to assure us of his real presence with us there, in that arena? Such statements from the pop star, statements like like "Hello Chicago!", are practically de rigueur. The concert audience seems to crave signs that the performance is, in some way, unique, that it is original, and here again is a quality that separates pop concerts and tent revivals from other traveling entertainments, where there's little expectation that each instance of the entertainment be unique. To the contrary, in the case of entertainments like touring Broadway shows, the spectators hope that the version they see will be as close to the original as possible: the touring version of a Broadway show continuously repeats the same performance at each stop along the way, and therefore the key quality is the performance's reproducibility. A similar situation obtains when an orchestra goes on tour: where technical virtuosity forms part of the performance's appeal, then reproducibility is essential. The same is basically true of freak shows and exhibits: the value inheres in the fact that the entertainment is the same as what everybody else saw. If you visited the Art Institute to view a traveling exhibit of Picasso paintings, you would probably feel disappointed to learn that some of the most important paintings, though part of the touring exhibit, had not been displayed at the Chicago installation.

Of course, each performance of a touring pop concert does repeat previous performances, but each performance must still, somehow, appear spontaneous and original. It's not that the audience believes the songs have never before been performed live, but that they want to believe the performance, as a whole, is somehow unique, that it is being given for them specifically, and that the star is expressing the real presence of his genius. And they want to believe that the experience of the performance has been meaningful to the star too: it's important that the performance feel like a shared experience between the star and his fans, a sense of shared experience that, tent revivals excepted, is largely absent from other traveling entertainments. For example, it's almost unthinkable that an audience would sing along to a touring Broadway show, or jump into a circus ring and try to tame a lion, but at pop concerts the audience commonly sings along to the music, and will storm the stage; stars often throw mementoes into the crowd, mementoes that are then furiously fought over like fetishes of the god, and some stars have even been known to stage dive into the floor pit

Shared experience, therefore, is certainly a hallmark of the pop concert, and at the 1975 show, part of that shared experience is generational, a shared sense, for example, that their generation has been fucked over by older generations.

I can't help but wonder to what extent the 1975 really are of this younger generation, though. They certainly try hard to cultivate that status. I was intrigued, however, by one of the slogans that appeared on many of the concert t-shirts: "Rock and roll is dead; long live the 1975". In interviews also, Healy frequently denies that the 1975 is a rock band, which I can get behind: to me they're a pop band. But that bit of sloganeering—doesn't it have the opposite meaning? After all, it's an allusion to the traditional proclamation made upon the death of a monarch: "The king is dead; long live the king". So isn't the 1975 really saying that they ARE rock and roll, that they are the new rock and roll, and the rightful heirs to that mantle? Who knows. Healy is notoriously coy about these things, which, to my mind, pushes him closer to the aestheticism of the (18)90s. For example, this sloganeering in which the band so heavily indulges, at first makes them seem like social activists, but interestingly the pace at which these slogans appear on the giant monitors accelerates throughout the show, so that by the end it was no longer possible even to read them, and the slogans, drained of actual social content, become pure form, pink camp, or angry dada—take your pick.

The show ended; the band packed it in, and eventually continued on to the next tour stop. (See Appendix C for what happened the following day.) When you leave the show, you don't really think about where the band is going next on its tour, just as you don't really think about where they came from before. I think that's part of the illusion of a traveling entertainment: it appears; it's a shared experience between spectators and performers; and then it's gone. You don't get to witness the crews building up the stage, or tearing it down and packing it up.

A traveling entertainment is a moving secret on a closed circuit, a disappearing trace on a disappearing map. All written records of it will be found to have been made in vanishing ink.

Appendix A: An Incomplete List of Songs That Were Hits for Multiple Recording Artists:

- Ain't That A Shame

Pat Boone (#1 in 1955); Fats Domino (#10 in 1955); Four Seasons (#22 in 1963); Cheap Trick (#35 in 1979). - All I Have To Do Is Dream

Everly Brothers (#1 in 1958); Richard Chamberlain (#14 in 1963); Clen Campbell and Bobbie Gentry (#27 in 1970). - All I Really Want To Do

Cher (#15 in 1965); Byrds (#40 in 1965). - At My Front Door

Pat Boone (#7 in 1955); El Dorados (#17 in 1955). - At The Hop

Danny and the Juniors (#1 in 1958); Nick Todd (#21 in 1958). - Ballad of Davy Crockett

Bill Hayes (#1 in 1955); Tennessee Ernie Ford (#5 in 1955); Fess Parker (#5 in 1955); Walter Schumann (#14 in 1955). - Banana Boat Song

Tarriers (#4 in 1957); Fontane Sisters (#13 in 1957); Steve Lawrence (#18 in 1957); Sarah Vaughan (#19 in 1957). - Band of Gold

Don Cherry (#4 in 1956); Kit Carson (#11 in 1956); Mel Carter (#32 in 1966). - Breaking Up Is Hard To Do

Neil Sedaka (#1 in 1962); Lenny Welch (#34 in 1970); Partridge Family (#28 in 1972); Neil Sadaka (#8 in 1976). - Can't Take My Eyes Off You

Frankie Valli (#2 in 1967); Lettermen (#7 in 1968). - Chapel in the Moonlight

Bachelors (#32 in 1965); Dean Martin (#25 in 1967). - Crying

Roy Orbison (#2 in 1961); Jan and the Americans (#25 in 1966); Don McLean (#5 in 1981). - Cupid

Sam Cooke (#17 in 1961); Johnny Nash (#39 in 1969); Dawn (#22 in 1976); Spinners (#4 in 1980). - Don't Be Angry

Crew-Cuts (#14 in 1955); Nappy Brown (#25 in 1955). - Don't Be Cruel

Elvis Presley (#1 in 1956); Bill Black's Combo (#11 in 1960). - Earth Angel

Crew-Cuts (#3 in 1955); Penguins (#8 in 1955); Gloria Mann (#18 in 1955). - Eddie My Love

Fontane Sisters (#11 in 1956); Chordettes (#14 in 1956); Teen Queens (#14 in 1956). - Enchanted Sea

Islanders (#15/1959); Martin Denny (#28/1959). - Fascination

Jane Morgan (#7 in 1957); Dinah Shore (#15 in 1957); Dick Jacobs (#17 in 1957). - Fever

Little Willie John (#24 in 1956); Peggy Lee (#8 in 1958); McCoys (#7 in 1965). - Fools Rush In

Brook Benton (#24/1960); Ricky Nelson (#12/1963). - Four Walls

Jim Reeves (#11 in 1957); Jim Lowe (#15 in 1957). - Frankie and Johnny

Brook Benton (#20 in 1961); Sam Cooke (#14 in 1963); Elvis Presley (#25 in 1966). - Freight Train

Rusty Draper (#6 in 1957); Chas. McDevitt Skiffle Group (#40 in 1957). - Go Away Little Girl

Steve Lawrence (#1 in 1963); Happenings (#12 in 1966); Dony Osmond (#1 in 1971). - Go On With The Wedding

Patti Page (#11 in 1956); Kitty Kallen and Georgie Shaw (#39 in 1956). - Goodbye My Love

McGuire Sisters (#32 in 1956); Fleetwoods (#32 in 1963); Paul Anka (#27 in 1969). - Graduation Day

Rover Boys (#16 in 1956); Four Freshmen (#17 in 1956). - He

Al Hibbler (#4 in 1955); McGuire Sisters (#10 in 1955); Righteous Brothers (#18 in 1966). - Hearts of Stone

Fontane Sisters (#1 in 1955); Charms (#15 in 1955); Bill Black's Combo (#20 in 1961); Blue Ridge Rangers (#37 in 1973). - Hummingbird

Les Paul and Mary Ford (#7 in 1955); Frankie Laine (#17 in 1955). - I Miss You So

Chris Connor (#34 in 1957); Paul Anka (#33 in 1959); Little Anthony and the Imperials (#34 in 1965). - I'm In Love Again

Fats Domino (#3 in 1956); Fontane Sisters (#38 in 1956). - I'm Into Something Good

Herman's Hermits (#13 in 1964); Earl-Jean (#38 in 1964). - I'm Walkin'

Fats Domino (#4 in 1957); Ricky Nelson (#17 in 1957). - Ivory Tower

Cathy Carr (#2 in 1956); Gale Storm (#6 in 1956); Charms (#11 in 1956). - Ko Ko Mo

Perry Como (#2 in 1955); Crew-Cuts (#6 in 1955). - Let Me Go, Lover

Joan Weber (#1 in 1955); Teresa Brewer (#6 in 1955); Patti Page (#8 in 1955); Sunny Gale (#17 in 1955). - Limbo Rock

Chubby Checker (#2 in 1962); Champs (#40 in 1962). - Long Tall Sally

Little Richard (#6 in 1956); Pat Boone (#8 in 1956). - Look For A Star

Garry Miles (#16 in 1960); Billy Vaughn and His Orchestra (#19 in 1960); Garry Mills (#26 in 1960); Deane Hawley (#29 in 1960). - Louie Louie

Kingsmen (#2 in 1963); Sandpipers (#30 in 1966). - Love, Love, Love

Clovers (#30 in 1956); Diamonds (#30 in 1956). - Love Me Tender

Elvis Presley (#1 in 1956); Richard Chamberlain (#21 in 1962); Percy Sledge (#40 in 1967). - Man With The Golden Arm

Richard Maltby (#14 in 1956); Elmer Bernstein (#16 in 1956); Dick Jacobs (#22 in 1956); McGuire Sisters (#37 in 1956). - Me and Bobby McGee

Janis Joplin (#1 in 1971); Jerry Lee Lewis (#40 in 1971). - Mona Lisa

Carl Mann (#25 in 1959); Conway Twitty (#29 in 1959). - Mr. Wonderful

Sarah Vaughan (#13 in 1956); Peggy Lee (#14 in 1956); Teddi King (#18 in 1956). - Naughty Lady of Shady Lane

Ames Brothers (#3 in 1955); Archie Bleyer (#17 in 1955). - No Arms Can Ever Hold You

Georgie Shaw (#23 in 1955); Pat Boone (#26 in 1955); Bachelors (#27 in 1965). - No More

De John Sisters (#6 in 1955); McGuire Sisters (#17 in 1955). - Ode to Billie Joe

Bobbie Gentry (#1 in 1967); King Curtis (#28 in 1967). - Only You

Platters (#5 in 1955); Hilltoppers (#8 in 1955); Franck Pourcel's French Fiddles (#9 in 1959); Ringo Starr (#6 in 1974). - Papa's Got a Brand New Bag

James Brown (#8 in 1965); Otis Redding (#21 in 1968). - Party Doll

Buddy Knox (#1 in 1957); Steve Lawrence (#5 in 1957). - Pledge of Love

Ken Copeland (#12 in 1957); Mitchell Torok (#25 in 1957). - Pledging My Love

Johnny Ace (#17 in 1955); Teresa Brewer (#17 in 1955). - Raunchy

Bill Justis (#2 in 1957); Ernie Freeman (#4 in 1957); Billy Vaughn (#10 in 1957). - Red Roses for a Blue Lady

Vic Dana (#10 in 1965); Bert Kaempfert (#11 in 1965); Wayne Newton (#23 in 1965). - Red Sails in the Sunset

Platters (#36 in 1960); Fats Domino (#35 in 1963). - Rip It Up

Little Richard (#17 in 1956); Bill Haley and His Comets (#25 in 1956). - Seventeen

Fontane Sisters (#3 in 1955); Boyd Bennett and His Rockets (#5 in 1955); Rusty Draper (#18 in 1955). - Silhouettes

Rays (#3 in 1957); Diamonds (#10 in 1957); Herman's Hermits (#5 in 1965). - Since I Met You Baby

Ivory Joe Hunter (#12 in 1956); Mindy Carson (#34 in 1956). - Sincerely

McGuire Sisters (#1 in 1955); Moonglows (#20 in 1955). - Singing the Blues

Guy Mitchell (#1 in 1956); Marty Robbins (#17 in 1956). - Sittin' in the Balcony

Eddie Cochran (#18 in 1957); Johnny Dee (#38 in 1957). - Soft Summer Breeze

Eddie Heywood (#11 in 56); Diamonds (#34 in 56). - Stranded in the Jungle

Cadets (#15 in 1956); Jayhawks (#18 in 1956); Gadabouts (#39 in 1956). - String Along

Fabian (#39 in 1960); Ricky Nelson (#25 in 1963). - Teen Age Prayer

Gale Storm (#6 in 1956); Gloria Mann (#19 in 1956). - Three Bells

Browns (#1 in 1959); Dick Flood (#23 in 1959). - Tonight You Belong to Me

Patience and Prudence (#4 in 1956); Lennon Sisters (#15 in 1956). - Tutti Frutti

Pat Boone (#12 in 1956); Little Richard (#17 in 1956). - Tweedle Dee

Georgia Gibbs (#2 in 1955); Lavern Baker (#14 in 1955). - Unchained Melody

Les Baxter (#1 in 1955); Al Hibbler (#3 in 1955); Roy Hamilton (#6 in 1955); June Valli (#29 in 1955); Righteous Brothers (#4 in 1965). - Very Special Love

Debbie Reynolds (#20 in 1958); Johnny Nash (#23 in 1958). - Wake the Town and Tell the People

Les Baxter (#5 in 1955); Mindy Carson (#13 in 1955). - Wayward Wind

Gogi Grant (#1 in 1956); Tex Ritter (#28 in 1956). - Woman in Love

Four Aces (#14 in 1955); Frankie Lane (#19 in 1955). - Wringle, Wrangle

Fess Parker (#12 in 1957); Bill Hayes (#33 in 1957). - Young Love

Tab Huner (#1 in 1957); Sonny James (#1 in 1957); Crew-Cuts (#17 in 1957).

Appendix B: Journey to the 1975

My trip to see the 1975 on their Brief Inquiry into Online Relationships tour began, appropriately enough, online. I had trouble booking the ticket through Amtrak's website, which kept dropping my connection every time I reached the payment screen. My patience exhausted, I drove to the station to buy my ticket the old fashioned way. At the station, the ticket window was open, but no lights were on inside the booth. A man was sitting there, though, on a stool, legs crossed, filing his nails. He did not acknowledge me as I approached, so I asked, "Is the ticket window open?" He rolled his eyes and sarcastically lisped, "No, I'm just sitting here because I enjoy the view of the empty waiting room. Yes it's open!" I considered pointing out that, by turning on at least one light, he might helpfully signal this fact to customers, but I quickly realized there was nothing to be gained in doing so. Instead I just asked him for a ticket from Champaign to Chicago on May 8, with a return ticket the following day. He sighed deeply, heaving his shoulders, as though exasperated by all of mankind's stupidity. He said, "Couldn't you just do this online?"

Amtrak is chronically unreliable. The 10:00 a.m. train usually runs late, but even when late it not uncommonly arrives well before the 6:00 a.m. train. The 10:00 a.m. train is usually full, often overbooked, although waiting passengers never really know for sure whether that day's train will be among the overbooked ones. There's a slight scent of ozone in the waiting room, which feels electrically charged with uncertainty and apprehension and anxiety. I take benzodiazepines to deal with anxiety.

The 1975's frontman, Matty Healy, has said that coming off benzodiazepines is worse than coming off heroin.

A college town like Champaign resembles, in many respects, the border towns and occupied cities of novels and films. It has a large transient population, and a permanent bureaucracy that lives off this population, often in an exploitative capacity, even when, and perhaps especially when, the exploitation is not, strictly speaking, articulated as such. Oddly, this similarity to border towns becomes most visible to me when I'm waiting for the ten o'clock train. Because of the university, there are always crowds of students traveling back and forth between Chicago and Champaign. At the train station, the dominant feelings, which presses upon you, are of waiting and frustration. Anxious waiting, hopeful waiting, desperate waiting, impatient waiting. Waiting, of course, for a train, but the train's arrival is always a matter of such uncertainty that the object of this waiting, the focus of our attention, bleeds out into a malaise that becomes general, and could be the malaise of characters in a border town spy novel. We passengers sit there, furtively, pretending to mind our own business, staring into our cell phones, fidgeting with text messages, reading our books; we all appear to be doing nothing, which has the side effect of making everybody look slightly suspicious: that man over there could just as easily be a stranded refugee waiting for the bribe to go through, or else waiting for the bribed bureaucrat to produce the necessary visa, or else waiting for the arrival of the steamer that will carry him to safety; or perhaps the captain of this steamer must himself be bribed before the fugitive will be allowed to board the ship; he could be a spy waiting to receive an encrypted dispatch from his handler; he could be a saboteur carrying the purloined attack plans; he could be an assassin waiting for his mark; he could be a drug lord waiting for the return of his mule; we could all be captives in a border town surrounded by enemy forces, waiting for the bombardment to cease, and for the invading army finally to occupy the city. We could all be waiting for something to happen, for the end to come, or the beginning to begin.

This waiting, it is the mood of:

- Company Station in Heart of Darkness

- Rick's Cafe in Casablanca

- Vienna in The Third Man

- Saigon in Dog Soldiers

- Odessa in Journey to the Black Sea

- San Pablo in Ride the Pink Horse

- The Hotel Savoy in Hotel Savoy.

In the back of everyone's mind, causing no small amount of consternation, is the grim reality of festival seating, which means first-come, first-served. They call it festival seating for a reason, and it has nothing to do with the experience being akin to a festivity: it's the experience of the uncontrollable crowd, and to experience festival seating is finally to understand the etymology of the word "crowd", which comes from the verb "to crowd", which means to press in upon. As soon as the station agent announces the train's arrival, people begin crowding the platform entrance in a giant crush of physical human determination, bearing only the slightest resemblance to a line. Passengers regularly cut in line, with a look that insolently dares you to protest.

Amtrak's coach cars use the standard, 2+2 airplane seating layout. Most passengers, even if traveling alone, want an entire two-seat bay to themselves, so that if you are traveling with a companion, and you would like to sit beside your companion on the train, then you had better get yourself to the front of the line, because each lone rider ferociously pounces on any empty seating bay, hoping against hope that the adjacent seat will remain unoccupied; these passengers use one or more of the well-known stratagems for effecting this: they either place their luggage in the empty seat, or they falsely claim the seat is already taken, or they make themselves appear as disagreeable as possible; or they cover their ears with headphones and pretend not to hear inquiries from other passengers asking if they can have the empty seat. This chicanery goes on even when the conductor has announced repeatedly that the train is overbooked, and that all available seats will be taken. The conductor, for his part, rushes people to find a seat and sit in it, because the train is always behind schedule and it's his job to make the station stops as brief as possible, usually about five minutes (and that's for both detraining passengers and boarding passengers). The conductors can be brusque, probably out of necessity, but it's not difficult to imagine them using cattle prods on finicky passengers. In the rush to find a seat, boarding passengers will scout each car, and in each car must decide quickly whether to take one of the available seats, or else gamble on finding a better seat in another car, "better seat" meaning a seat in an empty bay, or at least a seat beside a more attractive person. If the train really is overbooked, then the conductor puts surplus passengers in the club car, and before the phrase "club car" conjures visions of pre-consolidation club cars in classic movies, let me assure you that Amtrak's club car is nothing like what you see in the movies. It's more like a roller skating rink snack bar, only not as agreeable as a rolling skating rink snack bar.

Once all departing passengers are off the train, and all boarding passengers are on the train, the train resumes its journey, whether or not all boarding passengers have found a seat. It probably serves as a final hint that they should do so as quickly as possible. I look around to see all the people with whom I will be sharing this experience, this train ride, and they are mostly younger than I am, but some are older. Many of the songs on the 1975's latest record are about past selves and future selves, and I think about this when I look around the train car, especially my past self, which is easier to see in the faces of my fellow passengers than is my future self. In either case, I look around and I wonder how many of these fellow travelers are already on drugs, at mid-morning.

In 2017, Healy revealed that he had successfully completed drug rehabilitation, after four years of addiction to heroin.

My favorite part of the trip from Champaign to Chicago is the moment when the train emerges from beneath McCormick Place, and suddenly you see the city arrayed before you, with grand old Soldier Field to your right, the rocket-like Lake Shore Drive traffic racing around its walls. The train then curls west into the city, through obscure neighborhoods, between loft apartments into which you can see through open windows. The train then enter a bizarre no-man's land of endless fields overgrown with weeds and littered with industrial wreckage.

On their own journey, the 1975 would have been entering the city from the north, having performed the previous night in Minneapolis.

I am not a city dweller, and have no experience of the city except as tourist or visitor, the latter which I take to be something between a tourist and a resident, somebody in the city on a specific errand, or else there to see a friend, which means being drawn into closer proximity to the lives of real residents, for whom the city is not principally a destination of leisure. But I have never actually lived in a city and there is much about city life that I find vexing. For example: the practice of taking taxis. I realize that not all, or even most, city dwellers regularly use taxis, and yet I assume most city dwellers possess at least a passing familiarity with taxi life. When I, for example, visit friends in a city we usually take taxis to night clubs and restaurants, and my city friends always seem to find the whole experience unproblematic. I myself am never quite comfortable with taking taxis. It's more the idea of taxis that bothers me. Taking taxis feels almost socially unacceptable to me: paying somebody to drive me around the city. In all the towns where I have lived, people drive themselves, or they walk or bicycle. Sometimes they ask a friend for a ride. But to sit in the back seat of an automobile while a stranger chauffeurs me--I become painfully aware of class stratification, and maybe that's a good thing, this lifting of the veil of false egalitarianism and false solidarity with the poor and marginalized that characterizes so much of the life where I have lived for most of my adult life, where even support staff are expected to address the dean by his first name, and we all mostly pretend that income inequality happens to OTHER people, even when the unions go on strike and the well-paid faculty solemnly pledge their support of the strikers, without actually offering to take a cut in their own pay, and everybody wears blue jeans and pretends to have just enough money to live comfortably, where conspicuous consumption is outré, unless it relates to travel or organic, fair-trade food.

Unfortunately, as a tourist in a city, especially a tourist with luggage, I'm thrown into the taxi life, and it's horrible. It's always horrible to confront your guilt and hypocrisy, and I try to smooth everything over by using the tactics that seem to work so effectively for the well-off where I am from: I attempt to engage the driver in chit-chat, which is almost always laborious and painful for both parties, especially when the driver speaks very little English, and I of course speak no language but, so that my guilt increases until, at the end of the ride, I invariably tip extravagantly, to assuage my guilty conscience.

All four members of the 1975 are multi-millionaires. The third track on the band's debut long player is called "M.O.N.E.Y.", and seems to be about designer drugs.

Unlike taxis, Ubers are a consistely pleasant experience, by which I mean that I actually look forward to taking an Uber. I still, ultimately, tip the Uber driver excessively, but from an more complex set of reasons that I do not entirely understand--possibly self-interest is an important factor, since the driver rates me as a customer, though I'm told the driver does not see his tip until after he has already rated the passenger. I have found that that, in every case, the Uber experience has been vastly more agreeable to me than the taxi life.

I was staying at the Hotel Knickerbocker, was built in 1927. (For a time the hotel was owned by Hugh Hefner.) I love old hotels, and the Knickerbocker is sort of my ideal of an old hotel, mainly because it has a lobby with a mezzanine and a bar where you can get excellent cocktails. The Knickerbocker is right across Walton Street from the Drake Hotel, which has far superior pedigree, but honestly I find the Drake's lobby to be shockingly dingy, and that goes for their famous Palm Court as well. The restaurant where guests take their buffet breakfast is also quite dingy. The guest rooms at the Drake are impeccable, however: spacious, clean, and decorated in an updated Federal style that elegantly complements the building's exterior. The hotel is adjacent to the old Palmolive Building, which, with its revolving beacon, once crowned most postcard vistas of Michigan Avenue. Interestingly, Hefner also once owned the Palmolive Building, and he wrote quite poetically about it, "One of the most important symbolic connections with the city was the beacon on the top of the 919 N. Michigan Ave. building. When we were kids, we could see that beacon sweeping across the sky at night. For me, it was like the wail of a railroad train passing by, part of that mystical yearning of youth and adolescence." Unfortunately, a monstrous piece of sixties architecture, the John Hancock Building, was built and now completely obstructs the view of the older, art deco landmark.

The chaotic festival seating of the train made a weird contrast with the reserved seating at the arena. An arena organizes a crowd, it sorts and sifts the crowd. Each ticket holder must enter through his assigned gate (there are 8 gates that encircle the arena), so that you are funneled and channeled until you come to rest in your assigned seat, like one of those toys into which you drop a marble. The word "arena" originally referred to the center of an amphitheater, where gladiatorial contests were staged for the enjoyment of the crowds. As I mentioned above, the word "crowd" comes from the verb "to crowd", which means to push or press in upon. And yet stage presence itself implies pressing upon a crowd, which itself means pressing. I would describe Healy's stage persona as camp, except that camp should be empty of ideological content, whereas the 1975 are very political, very socially relevant.

For the concert, I wore: a brand new pair of dark blue Levi's, a white undershirt, a black Arc'teryx base layer, a grey Alternative Brand Throwback Champ sweatshirt with blue sleeve stripes and blue piping, a navy blue Arc'teryx hooded jacket with red lining, and New Balance sneakers. I spent a lot of time on my outfit, and the look I was trying to achieve was "ordinary guy who didn't spend any time on his outfit—just threw on whatever was lying around". Desperate? Yes. Pathetic? Yes.

Appendix C: What Happened Next

The next day I was slightly hungover. My train back to Champaign was not scheduled to leave until about four. My hotel was just off Michigan Avenue, the so-called "Magnificent Mile", which is neither magnificent nor a mile. With a few exceptions, the building stock lacks distinction. The Magnificent Mile bases its claims to magnificence, I believe, on the retail options. For a Midwesterner like me in the days before the World Wide Web, there was something, I must concede, something magnificent about this orgy of shopping. Many designers have store fronts here, something almost unheard of in the Midwest, but the whole package is so touristy—I can never really buy into it. Are we really to believe that the very rich (and to be sure Chicago ha its share of the very rich) come down to Michigan Avenue for their shopping? That they rub shoulders with this hoi polloi, the gawking families from Davenport, Iowa or Fon du Lac, Wisconsin? Walk just one block west, to Rush Street, and you get the feeling that it's here, and probably in neighborhoods farther north, where the affluent Chicagoans do their shopping, if indeed they do it in Chicago at all. As for the actual shopping, it's so different from what many of us will have remembered. Now, I wander almost aimlessly, gazing upon merchandise that once would have delighted me, but now just sort of intrigues me, because I know that I can buy it just as easily, and, at Chicago's 10% sales tax, far less expensively, online. I furthermore would not have to schlep my purchases around town and onto the train back home. The in person shopping experience remains important for clothing and especially shoes, and even then it's for the luxury of trying the garment on--for shoes, this latter being essential still.

Notes

1. Dorian Lynskey, "Here Lies The 1975," Billboard, August 4, 2018, 36-43.

2. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, "Kubla Khan," Christabel (London: John Murray, 1816), 58.

3. "A Brief Inquiry into Kinesys for The 1975," Live Design, March 11, 2019.

4. Alfred Tennyson, "The Lotos-Eaters," Poems, (London: Edward Moxon, 1859), 146.

5. D.H. Lawrence, Women in Love (London: Martin Secker, 1921), 42-43.