A Few Memories from My Six Months at Marshall Field’s, Rockford

Introduction

My parents moved to Rockford, Illinois during my final year of college, but I’m from a small town, in a rural county, so Rockford was a significant change, fifty times as large as my hometown, and three times as large as the town where I attended college. I wasn’t naïve enough to consider Rockford a “big city,” but it was certainly the biggest city I had ever lived. Rockford also intrigued me because it had a Marshall Field’s department store. Before moving to Rockford, I knew Marshall Field’s mainly from its famous State Street store,1 and my idea of Field’s was highly romanticized, thanks to the State Street store’s opulence, its grandeur, the abundance and extravagance of merchandise…attributes that could be gathered under the name of “luxury.”

Luxury resists my attempts to define it. Possibly it doesn’t so much resist definition as simply elude it, like liquid eluding the grasp of hands. Luxury can be experienced, even imagined, but not easily subjected to reason. It draws to itself great irrational forces, and very likely dominates those who, because they are not wealthy, can only imagine its pleasures: in the crucible of imagination, luxury becomes ever more magnificent the longer left unchecked by more rational considerations.

The few who can actually afford luxury might well find it, in its concrete forms, somewhat disappointing: when we purchase a luxury product, it ceases to be an idea, an otherly object, desired but not possessed; taken home, unwrapped, it joins the mundane. I suspect that those who can only imagine luxury are often more susceptible to its allurements than those with the means to possess it. Luxury probably has more than a little in common with religion, and shares many of the qualities that Marx ascribed to religion, its capacity to create “illusory happiness,” the “self-consciousness and self-esteem of man who has either not yet gained himself or has lost himself again.”2

Luxury and religion both depend upon faith and imagination: we have faith that luxury exists, and we imagine its gratifications. What besides faith and imagination can make us believe that one wool sweater is luxurious, another simply functional? It is surely no coincidence that religiousness tends to increase as household income decreases.3 When Mary of Bethany anointed Jesus’s head with expensive perfume, many of the disciples objected on the grounds that the perfume was worth more money than most workers earned in an entire year; the perfume, they argued, should have been sold, and the money given to the poor, in keeping with Jesus’s own teachings. Responding to these objections, Jesus made Christianity’s first defense of luxury, stating that “Ye have the poor with you always, and whensoever ye will ye may do them good.” If luxury is conceptually akin to religion, then the the Marshall Field’s State Street store might not unreasonably be compared to the great cathedrals of European Christianity, which overawe visitors, sometimes eliciting a belief in god that no learned treatise could achieve. And if modern luxury is similar to religion, then it would be a sacramental religion, for the brand name consecrates the garment, just as the words of the priest consecrate wafer and wine.

Whatever luxury seems to be, or we believe it to be, it is without doubt a big business. In the United States, luxury goods generated over $78 billion in revenue last year.4 Like all businesses, those that traffic in luxury continuously try to increase their profits, and at some point this increase can only be accomplished by expanding their markets. But how do you expand the market for goods that are valued in part for their exclusiveness? Fashion labels have tried to solve this problem by creating “brand extensions” (sometimes called “diffusion lines” or “bridge lines”). For example, Giorgio Armani is haute couture; Emporio Armani and A|X Armani Exchange are upscale streetwear: expensive, yes, but accessible to aspirational consumers. Comme des Garçons probably has more brand extensions than any other,5 but many luxury labels have them. When Waterford Crystal introduced a brand extension, which they called “Marquis by Waterford Crystal,” they demanded that retailers display and advertise the Marquis by Waterford line separately from original Waterford Crystal: customers must be under no misapprehension that Marquis by Waterford was equivalent in any way to original Waterford Crystal.6 The value of the brand name must be protected.

Luxury hotels use a similar strategy, called “brand segmentation.” When you pull off the interstate and choose to stay at a Hilton Garden Inn, or a Hampton by Hilton, you don’t really think it’s going to be like staying at the Beverly Hilton, but the Hilton name might well lead you to consider it a more attractive option than, say, the Comfort Inn. With both brand segmentation and brand extension, the purpose is to trade down, to exploit the cachet of the core brand, and the desire of aspirational consumers to own something from a luxury label; simultaneously, the brand extension protects the crucial exclusivity of the luxury brand, insulates it from the taint of the common. There exists, however, a point of diminishing returns, and, finally, a market threshold beyond which these strategies deplete and degrade the value of the core brand: when everyone is wearing garments and accessories that bear some version of the “Armani” or “Comme des Garçons” name, then those labels’ true luxury lines begin to lose their hard-earned prestige, and with the prestige they will lose loyal customers.7

In 1998, when I was 23, I worked in Rockford, Illinois, at the Marshall Field’s department store, Cherryvale Mall. It was almost nothing like the famous State Street store, which was a grand palace of luxury, and in that respect it typified the problem of luxury brands in a mass market. Marshall Field’s, like most department stores, never attempted brand segmentation, so that the relationship between its State Street store and its twenty mall stores was one of equivalence, at least in terms of brand equity: the Rockford store, the Oakbrook store, the State Street store, the Michigan Avenue store—they were all, in theory, equally Marshall Field’s department stores. The company had no way to distinguish the premium luxury stores from those stores that were merely upscale (for their respective markets). It was almost inevitable that these mall stores would, at some point, become a drag on the “Field’s” brand. It’s true that some of the mall stores, like the one at Oak Brook, probably did qualify as luxury department stores, but the status of the mall stores varied wildly, and even Oak Brook was, at the end of the day, still a “mall store.” Even worse, in a way, the companies that managed the shopping malls referred to their malls’ department stores as “anchors,” suggesting that all the boutique stores in the mall—from the Gap to the Orange Julius, were partaking of that anchor store’s brand equity. A shopping mall with only a Sears and a J.C. Penney for anchors was hardly the same as a mall that could boast a Field’s and a Nordstrom and a Nieman Marcus.

Of all the mall stores, the Rockford store must have been the lowliest in status. Opened in 1973, it was 115,000 square feet, by far the smallest of the Field’s mall stores, which tended to be about 250,000 square feet.8 Among the twelve Illinois cities with a Marshall Field’s, Rockford ranked last or second-to-last on almost every socio-economic indicator.9 By 1998, Rockford’s fortunes were on a fast, probably irreversible decline, and when I moved there it seemed a strange location for Marshall Field’s, which still claimed to be a luxury department store.10 Really, the whole chain was coasting on former glory, but luxury is largely about what consumers believe to be true, or even what they want to believe is true, and many people in Rockford needed to believe that Field’s was a luxury department store: its presence in Rockford defied the reality of rustbelt blight all around them, confirmed their belief that Rockford was something other than a Metropolitan Statistical Area (SMSA) with an average household income well below the national average.11

The expression “there are no atheists in foxholes” comes to mind, and one might say that there are no egalitarians among the lower middle classes, who sometimes cling to snobbery and class distinctions—the narrower the spread, the finer the divisions—with a fierceness that would seem to defy reason. But defiance is a human response to adversity, and the Rockfordians who believed in the idea of Field’s were rather like Job on his dung heap; the whole idea of Field’s was probably more important to them than it could ever be to the people of Oak Brook or Lake Forest.

Rose

I applied for the job in June, and immediately received an invitation to a “group job interview,” conducted by a woman named Rose, the store’s head of Human Resources. I had never previously participated in a group job interview; in fact, I had never even heard of such a thing. Only later did I understand that the store hired hundreds of people each fall, and terminated most of them shortly after Christmas, the deep inhale and deep exhale of chain retailing: inhale the good, exhale the bad, let all that negative energy go, as a yoga instructor might say. The group job interview was my first exposure to the reality of Marshall Field’s: its workforce, like the merchandise it sold, was mass produced and not intended to last very long, however elegant it might appear on the rack. Rose conducted the group job interview.12

Group job interviews were obviously the most efficient means of processing the massive number of job applications the store received. For the applicants it was certainly a degrading experience, which, even if not its primary purpose, must have served a useful function, reminding us all that a lot of people wanted a job, and that we might well fight a cage match to secure one.

The group interview also reinforced our interchangeability as workers: each of us could be easily swapped out for newer parts at any moment. Though I never knew at the time, this dependence on cheap, unskilled, part-time, seasonal labor had been the principal fact of the department store workforce since the 1960s.13 How immense must have been the burden of Rose’s responsibility, presiding over this huddled humanity petitioning her for employment. But did the Lord himself not say, blessed are the poor, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven? Imagine how this awesome responsibility irradiated Rose: we wanted jobs, needed jobs, and she was in a position to supply them. Even St. Peter, from his throne at the gates of heaven, must have looked down upon her with some wonder at such a burden devolving to one mere mortal.

Rose explained to us that, at Marshall Field’s, there are no customers, only guests. And Field’s personnel, therefore, gave “guest service,” not “customer service.” She pronounced “customer” as though swallowing a rancid piece of food, that first syllable “cust” especially offensive, like a jagged bit of bone that sticks in the throat. No, there were no customers at Field’s, only guests.14 When she spoke, she sounded by turns scolding and then weary, as if worn down by having repeatedly to explain obvious truths, for example, “The store is beautiful; the merchandise is beautiful.” Despite the fact that money is the very lifeblood of retail, she clearly found the subject distasteful, unpleasant even, but mention it she must: we would earn a minimum wage if hired; we would receive a 20% employee discount on all merchandise, if hired. She was happier talking about compensation in more abstract terms, for example the company’s 401K program and other job benefits for which (she failed to mention) none of us would ever qualify since Field’s only offered these benefits to full-time workers, of which the store employed very few, and among which it was highly unlikely any of us seasonal applicants would ever be fortunate enough to count ourselves.

She gave a lengthy speech on the strict employee dress code; it seemed to me she was jumping the gun a bit there, as none of us had yet been hired. I wondered if perhaps the dress code presentation was an easy way to deter unsuitable applicants—unsuitable because many either couldn’t or wouldn’t acquire such expensive costume for such a low-paying job. Or maybe it was part of the store’s mystique that she was trying to sell us, or perhaps she knew that everyone in the room would at some point be offered a job so she might as well dispatch the dress code lecture then-and-there. Men were required to wear a business suit, solid colored dress shirt, and dress shoes with matching dress belt. Pants must have no visible stitching or seams. Back pockets on pants must be welt, side pockets on pants must be vertical. I don’t remember much about the women’s dress code except that they were not allowed to wear open toed shoes; Rose said, with a shudder of revulsion, that “our guests do not want to look at your toes,” as though Field’s guests might well wish to look at other people’s toes, but not for anything in the world would they ever want to see ours.

The whole ceremony of the dress code also helped reinforce the “many are called, few are chosen” theme she had begun developing much earlier. When speaking of the dress code, she gave a magnificent performance, one moment rapturous, another moment appalled, shocked by our ignorance, worn down by the need, always the same need!, to raise us from ignorance. Of course, she knew Jesus had said the poor would always be with us, but oh, she must have thought, He said nothing about how to manage them!! Nor was it particularly easy for us: my first two paychecks went entirely toward a single, dress-code-compliant suit.

After the group interview, I heard nothing for almost two months. Then, in late July, I received the call! Rose offered me a job as part-time Associate in the Kids’ Department. An associate was essentially a salesperson, or sales clerk, or simply a cashier, depending on the associate’s level of motivation. I rarely rose above the level of cashier, cashier in a business suit. Kids’ Department associates did not work on commission, like some departments,15 so motivation never amounted to much. My chief motivation was not to be fired. I don’t recall ever pushing guests to select particular products, so I worked well below whatever level of skill the term “associate” was intended to conjure in guests’ minds. There must have been market research showing that the “associate” title helped raised the tone of the store, that customers preferred to be waited on by people with ersatz-professional job titles, which I must admit did pair nicely with the dress code. Slapping the label “associate” onto sales staff probably helped conceal the grime of the job’s drudgery. People don’t like to feel guilty when buying luxury items, and it’s nicer to think that the people serving you are professionals, earning a decent salary with benefits, and prospects for advancement in their careers.

Rose had begun working at Field’s in 1973, when the store (and the mall which it helped anchor) first opened. I would guess that she had begun as a salesperson, and probably clawed her way to this highest position for which her high school diploma qualified her. Rose the Sybarite, Rose the True Believer! A believer in Field’s, and a believer in the gospel of luxury. And most importantly, a believer that the Rockford Field’s was a luxury department store. If she had ever believed otherwise, she would not now be shaken in her faith, and as the Head of Human Resources, a priestess of the religion, she enforced its commandments with the zeal of a convert.

Barb

I began during the back-to-school season, and on my first day of work I reported directly to my department where I met Barb, who was our department’s sales leader. A sales leader was the department’s de facto manager, though not the actual manager. The actual managers formed an elite, and remote, caste within the store: they kept themselves a little mysterious, one knew they possessed power, but its nature and responsibilities remained obscure. I don’t know how frequently our manager visited our department, but I rarely saw her. When she did appear you were reminded of the important role processions once played in monarchies, the sovereign presenting herself to her subjects, a symbolic assertion of power and legitimacy. You were also reminded that, in the story by Hans Christian Andersen, the emperor chose a royal procession as the occasion on which to display his new clothes.

Barb’s role had no symbolic content; it was purely functional, and could not be consolidated through symbolism or ritual. Even her office was the essence of function: a desk, a chair, and a filing cabinet in the corner of our department stockroom, and it was here that she and I had our first meeting, which did not go well. I had applied for the job in June, but did not receive an offer until almost August; in the meantime I had made travel plans with a friend from England. When Rose offered me the position, I told her about this scheduling conflict, and she assured me it would be no problem. Evidently she meant it would be no problem for her. For Barb, however, it was very much a problem, as these travel plans would interfere with the staffing schedule, and the staffing schedule was her principal responsibility as sales leader, whatever higher achievements her job title itself might have suggested. She was angered by this news, and I had the impression that she would have liked to fire me on the spot. In retrospect, I can understand her frustration: August was back-to-school season, an especially busy, and important, time for the Kids’ Department. It really was thoughtless, reckless even, of Rose to assure me that a lengthy absence during this period could be no problem whatsoever.

Barb was very thin, and short; she always looked exhausted, but she also possessed an extraordinary nervous energy, a spastic agitation, like somebody who needs rest but keeps herself going with coffee and diet pills. There was an air of volatility whenever she was in the department, as if she carried undetonated nitroglycerin bombs which might explode any moment. And when she left, you could feel everything relax. For a few weeks I thought of her power as near-absolute, but soon learned, through department gossip, that she had long been at loggerheads with the real management, which is to say the titled and vested management, and that the situation, for her at least, had reached a critical stage.

The more I learned about the way the store worked, the better I understood why Barb could be so brittle in manner. As a sales leader, her position was inherently insecure, since sales leaders served at the pleasure of their managers, and even a well-liked sales leader could be easily ousted. To make matters worse, she had many enemies in the store. Barb always seemed to be expecting an ambush, and she consequently lacked the gracious manner that was supposedly the hallmark of Marshall Field’s. She clearly came from a different retail tradition; she had mastered the feverish hustle of sales, its hardscrabble, cutthroat competitiveness, and this ethos was out of place at Field’s. Or rather, it was out of place when revealed. Don’t mistake me: when it came to actual sales, she could produce a workable simulacrum of grace, but with colleagues she went straight to the point, rather like a poisoned dart. Yes, I think it can fairly be stated that Barb and Field’s were not well-matched, in part because Barb had taken its measure, and shrewdly grasped that, whatever might be true of other Field’s stores, the store in Rockford was different from a Sears mainly in the outward signifiers of luxury—the brand names, the fancy bags, the anachronistically strict dress code. Otherwise, its upscale pretensions were largely fraudulent. Some of the most ardent believers in this fraud were fellow employees, which must have been one reason she was so intensely disliked: people, hate it when you fail to disguise how well you grasp what they are really about.

Her competitiveness was with other departments, other sales leaders. She did not compete with her own associates; it was the department that concerned her. She would raid the store’s central supplies depot, hoarding supplies intended for guests who made expensive purchases, supplies like the famous green shopping bags, shirt boxes, sweater boxes, hat boxes, tissue paper, garment bags, card stock receipt envelopes, embossed gold seal stickers…all the appurtenances of luxury, or rather the props needed to stage manage the illusion of luxury. Barb could easily mount these sorties because our department was in the basement, and one of our storerooms connected with the supplies depot. In fact, ours was the only sales department directly connected in this way. All other employees had to request supplies from the shipping and gift wrapping counter, which connected with the same storeroom from the other end.

When training me, Barb stressed three main points. First in importance was turning up for shifts; second was turning up for shifts on time. The whole staffing schedule was like a Jenga tower, and it usually came crashing down at least once a week; when it did, the sales leader received a share of the blame. I was a very reliable employee, and, as a part-time worker with no friends in Rockford and no children to raise, I was usually available to pick up extra shifts, which made me especially valuable, since other workers were forever calling in sick (“calling off,” in the parlance of that particular workplace) or trying to give up their assigned shifts. Barb spent much of her energy enforcing the schedule.

The third point in training was the Field’s guest service script, which began with the associate greeting each guest who entered the department. The greeting was supposed to be informal, to engage the guest in conversation. For example, you didn’t just say “hello,” or “how are you today?” The latter might sound engaging, but could be easily parried by the guest with common responses like “fine,” after which it would become more difficult to prolong the engagement without coming off as pestering. Complimenting the guest on something she was wearing was considered a useful opener in some departments, as it could be easily transitioned into a discussion of related merchandise that the guest might find desirable, but this approach was less useful in the Kids’ Department since parents did most of the shopping on their children’s behalf.

After the greeting, the script required us to ask the guest what she was seeking, maybe asking a question slightly less direct, like “what brings you in today?” The idea was to cultivate a “friendly” rapport with the guest, while at the same time obtaining essential information that could be used in a targeted sales pitch. Once we had secured this all-important information (what the guest wanted or what the guest thought she wanted), we were to explore options in the department. The script stipulated that we must show them more than one piece of merchandise, even if—and especially if—the guest had already settled on something; this was the moment when we were meant to use our various upselling techniques, none of which I can remember because I never used them. Upselling is the practice of persuading guests to purchase something they don’t really want, or a more expensive version of something they do want. For example, the guest might have selected a store-brand sweatshirt, and upselling would be persuading the guest that she would be happier with the Hilfiger sweatshirt, which cost ten times as much money. Another part of the script was the expression of enthusiasm over the guest’s selections, or the admiring their choices, which was thought to be affirming, to remove doubt, and to minimize the risk that the guest would have second thoughts. Affirming strategies were important even after the actual sale, because guests could always return merchandise if they began to doubt the wisdom of their purchases, or if they found something they liked better elsewhere in the mall. Sales leaders like Barb were usually quite good at these techniques, even a little ruthless, to be honest.

Marshall Field’s enforced the guest service script through a sort of secret police, the “secret shoppers.” Secret shoppers looked like ordinary guests, and you never knew if the person who had entered your department was a secret shopper. If she was a secret shopper, then she would write a report after completing her visit, rating you on how well you performed each element of the guest service script, or whether you even tried. You never knew if you had “been shopped” (as was said) until your next shift, when you would find a secret shopper’s report in your mailbox. If you hit all the elements in the guest service script, then you received some sort of reward.

The purpose of the guest service script was not just to sell more merchandise; sales were a means to a far more important end: the overriding objective, especially with guests who hovered around the clearance racks and sale racks, was getting them to buy more than they could afford, and this part was important not only because it meant more sales, but also, and probably more importantly, because it meant the guest would have to buy on credit, and if the associate did his job well, then the guest would be buying on Field’s credit.

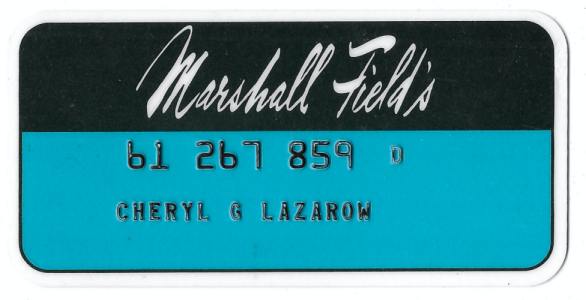

Which brings me to the significance of the Marshall Field’s credit card. Associates were pressured to open Field’s credit card accounts for guests; it almost seemed as though the store was more interested in these credit card accounts than in actual sales. When a guest was ready to pay, associates had to ask, ever so casually, “Will you be putting this on your Field’s card?” If the guest said no, then we had to feign surprise, and say, “Oh, well would you like to open a Field’s credit account today?” As if the lack of a Field’s card was the only reasonable conclusion one could draw from a customer’s choice not to use it. Before the guest could decline, we rolled into the many benefits of opening one, like Soviet tanks rolling into Czechoslovakia, beginning with the one benefit guaranteed to be the most tempting: by opening a Field’s credit card account, the guest would receive twenty percent off all purchases for the entire day, “That’s twenty percent on top of any other sales or discounts, and includes designer lines like Hilfiger which almost never go on sale.”

The Field’s credit card was important for a few reasons. First, Field’s made more money off a purchase if it did not have to pay a credit card company’s payment processing fee, an especially important consideration since few customers ever paid full price for anything, so most of what we sold was already at a discount. Second, the Field’s card enabled the company to earn interest, which could be as high as twenty percent, on the account balance. With high interest rates, the store could more than recuperate any money lost through discounts and other promotions.

The big (and possibly only) lure for the customer was the twenty percent discount on all purchases for one full day, but the card came with other, in my opinion basically worthless, “rewards” that we were supposed to tout. Some of these rewards included ostensibly-exclusive offers, invitations to members-only sale events, and extra discounts (fifteen percent) when a cardholder spent a certain amount in a single month (I think it was something like $500). Oh, and the guest would magically become a “member,” that country club fantasy, and whenever she used her Field’s card the associate would say, “Thank you for being a Field’s member.”

After talking up the Field’s credit card, and tempting the customer with the twenty percent daylong-discount, it was always embarrassing for both parties (the guest and the associate) when the guest’s application was declined. The credit check was handled right there at the “point of sale” (cash register) by swiping one of the guest’s other credit cards. It was embarrassing for the guest to be told that the application had been declined, especially after hearing about the simplicity of the process, and the immense desirability of undertaking it. The embarrassment to the guest was made even worse when the bad news had to be delivered in front of the guest’s family, maybe his children or girlfriend—anyone who might find it painful or humiliating or disappointing to learn, in public, that her dad or husband or boyfriend had insufficient credit. Sometimes other guests will have been waiting, with increasing impatience, to pay for their own purchases, and they would often sigh with frustration to learn that the long wait had, after all, been for nothing. The sigh of the snob who finds that she is forever being imposed upon by society’s deadbeats. You could almost see the thought bubble, “They’ll let anyone in this store these days,” as though the declined credit application was confirmation that standards had also declined.

To salvage the situation, the associate would give some obviously phony excuse about how the application could not be processed, due most likely to a computer glitch, but that the guest would be receiving the decision (really, the rejection) in the mail, and that she would receive a voucher for her full day of twenty percent discounts when she did receive his acceptance (=never), “as I’m sure you will.” We were really telling bald faced lies, but the purpose of those lies was to ease everyone’s embarrassment. Is it wrong to lie when you do it for a good reason?

These few rejections notwithstanding, Field’s would give a credit card to almost anybody, even if it meant extending a very short credit line. And yet we had many guests, from an older generation, who obviously considered the Field’s card to be a sign of membership in an exclusive club, which was of course how Field’s wanted it to be viewed. These guests would sometimes, with obvious pride, produce from their pocketbooks the Field’s credit card they had first been issued decades earlier, as if they expected it to elicit an extra level of white-glove service from us. These older cards were easily recognized because they looked nothing like a modern credit card, and guests who owned one clung to them jealously, because if lost the store would replace it with the current version of the Field’s credit card, and they’d lose this precious status symbol.

Most of these old cards were cracked, some held together with yellowing Scotch tape. I assume the store encouraged the holders of such cards in their flawed belief that the possession of one signified elegance, refinement…old money. What other reason could explain a policy that allowed thirty year old credit cards to remain in circulation, an obvious security risk for both the cardholder and the issuer (Field’s). Barb was a genius at indulging the vanity of guests who had these old Field’s cards. She would remark upon them, thank the guest for being a longtime Field’s shopper, engage the guest in conversation about gracious living, and nostalgic reminiscences of the State Street store, which invariably involved tea in the Walnut Room. In sharing these reminiscences, she was careful never to imply that she considered herself, in any way, the guest’s social equal, or that her memories of these past glories were from any perspective other than that of a worker and perhaps a tourist who had once permitted herself the extravagance of a trip to the State Street store, rather in the capacity of a pilgrim, and I wouldn’t be surprised if these reminiscences were completely fabricated; she was simply shrewd enough to grasp that guests who brandished these old cards craved recognition.

Barb was effective with customers, but a disaster when it came to coworkers. I’ve met few people in my life so embattled as she, and not long after I began she was unceremoniously deposed. Sales leaders seemed to be under enormous pressure, though the pressure’s objective eluded me. I had a feeling they were somehow responsible for the department reaching its sales goals, which would explain the the job title, but if so then that pressure was not effectively transferred to the associates under her supervision, at least not in our department, and I was never told that we had sales goals. It came as a shock to Barb when she was finally removed from her position as sales leader, and even worse when removed from the department altogether, transferred to Menswear on the main floor. From that time, she always looked diminished, vanquished, lost; the old fighting spirit had gone out of her. Because Menswear was adjacent to the first floor’s main aisle, I would often see her when I was leaving the store, if my shift ended before closing, and if she saw me she would intercept me, from the boundary of her department, which it almost seemed she had been forbidden from crossing, and she would try to tell me her side of the story. She reminded me a bit of the Ancient Mariner, who brings a curse upon herself; no hermit would shrive her, and she must evermore tell her tale to anyone who will listen.

Since leaving Field’s I have noticed in other workplaces that the person who actually runs a department or unit, the person deputized to make managerial decisions, often develops a sense of indispensability alongside a growing fund of resentment, the former acting as an Achilles heel, but the two together driving the person to ever bolder acts of insubordination.

Candice

The store manager, Candice, was the only person employed as a professional, in the sense that she moved to Rockford specifically for the job. Everyone else was either from Rockford, or, like me, happened to be living there. Candice was also the only person whose college degree was an actual qualification for employment—just the fact of having a college degree, not that her degree prepared her to manage a department store (she had majored in history and geography). An even more desirable qualification, however, was her impeccable pedigree. She was from wealthy Fairfax County, Virginia, and raised among the Washington elite: her father worked in the Ford Administration as Deputy Press Secretary, and then as Chief Pentagon Spokesperson for Donald Rumsfeld. In 1979 he took a job with Skokie pharmaceutical giant G.D. Searle as Senior Vice President for Public Affairs. At Searle he again overlapped with Donald Rumsfeld, who was serving as President and CEO. Monsanto acquired Searle in 1985, and her father retired from the company in 1990, the same year Candice took a position in Skokie as Assistant Store Manager of the Marshall Field’s there.

Candice, therefore, would probably have been no stranger to prestige, influence, and wealth. Donald Rumsfeld, and other Washington insiders would likely have been familiar names in her family, possibly even acquaintances and friends. And I must acknowledge that she possessed an undeniable noblesse oblige. Although I never formally met her, she knew my name, and at the conclusion of the Christmas Eve shift, she stood at the store entrance and wished each of us a Merry Christmas, calling us by name, and handing out wrapped boxes of Frango mints. I’m a little embarrassed to admit, but I felt flattered that she would know my name, and a little honored by the gift, even though I knew it probably came from unsold stock which, already wrapped in Christmas paper for last-minute shoppers, had, with the end of the Christmas shopping season, become unsaleable anyway. Still, I felt the idiotic glow and flutter that I have read about in accounts of people who have received Maundy money from the Queen, and who gush over her complaisance and graciousness. Maybe this daughter of the military elite, out there in Rockford, far from Washington, D.C., was like Haroun al Rashid, wandering in disguise among the common folk of the nation: while we all knew her to be the store manager, which was glory enough to be sure, none of us then knew that she also was at home among the thrones, dominions, principalities, and powers, the military caste that would, in only a few years, hurl the nation into its longest war.

Within the Marshall Field’s universe, the Rockford store was probably a kind of proving ground for aspiring management. Candice began her career as a buyer in the State Street store, was then promoted to Assistant Store Manager at the Oak Brook store, transferred to the Skokie store, and served a very short stint as Assistant Store Manager on State Street, after which she was sent to Rockford as Store Manager. The Rockford appointment, therefore, was a promotion in rank, but an undeniable downgrade in social status. No one with her pedigree would choose to live in Rockford, and at times she must have felt exiled.

For an organization with such a large workforce, the store had a surprisingly flat hierarchical structure, with the store manager at the top, and then five or six managers at the level beneath. The sales leaders, who certainly performed managerial functions, were in reality only associates with extra responsibilities, but also extra burdens. Rose, the head of Human Resources, was also part of the hierarchy, but I never knew where, exactly, she fit within it. Because of her access to secret information (much of which she would have collected from the store’s Loss Prevention Team, as well as confidential personnel files), she enjoyed unrivaled familiarity with Candice, who must have depended heavily on Rose for information, and this relationship made her seem to occupy a higher position in the store hierarchy than was probably the case. I had the impression she liked to believe that Candice considered her a friend, and Candice probably encouraged her in that fantasy. Small gestures would have sufficed to achieve it, such as permitting Rose to address her as “Candy,” even if, from Candice’s perspective, such signs of favor were as breadcrumbs from her table. I doubt Candice seriously considered Rose to be her equal in any respect, but Rose was not the only dupe of this fake familiarity.

The Last Week

For shoppers—sorry, guests!—the Christmas season ended on December 24th. When the store reopened on the 26th, there would be no more Christmas music broadcast throughout the store, and the prices on all-things Christmas would be deeply slashed. For workers, however, the Christmas season continued beyond Christmas Day. The first few days after Christmas were very busy with returns and exchanges, and with the movement of returned merchandise back onto the sales floor.

The season I worked was the year that Field’s introduced a new policy on returns. Previously, guests could return unwanted gifts either for store credit, or for a cash refund, as long as the guest had a gift receipt. This policy meant not only that Field’s would have to strike sales from the books, but also—and more damaging—that the store would have to refund, in cash, the full price paid for gifts that had been purchased with credit cards, and for which the store had paid the cursed credit card processing fees. The store could not recapture those fees if the guest took cash on the return.

In order to stanch the hemorrhaging, Field’s created a new policy stipulating that any merchandise returned with a gift receipt could only be refunded in store credit. The company expected the new policy to be unpopular, and their expectations were fully justified. The store steeled its workers against guest anger by actuating the myth of the genteel Field’s customer, the genteel guest who had wanted the recipient to receive a gift from Marshall Field’s, something elegant or luxurious, a gift of quality and good taste that only the Field’s imprimatur could guarantee. Regrettably, many gift recipients were unworthy of the people who gave them those gifts, and, it was implied, just wanted the cash, most likely to pay their rent, feed a drug habit, place a bet on the horses…use it for something other than what the gift giver would have wished. And so, the line in this new script, the script with which we were to repel the attacks of these barbaric shoppers, was that “The giver wanted the recipient to have something from Marshall Field’s, and therefore we can only refund the gift in store credit.” In the Kids Department, where I worked, the judgment was even more severe, since most of the returns were made by parents, and the gifts had often been purchased by grandparents for their grandchildren. The implication (and it was barely an implication) being that the parents were stealing their own children’s Christmas presents, and this new policy protected innocent babes from their own predatory parents. Many of my coworkers made such ad hominem comments about disgruntled guests, behind the guests’ backs, of course.

All those returns, all that discarded luxury, piling higgledy-piggledy on our service counters, like discarded husks or sloughed skin, awaiting its final destination, mostly consignment to the clearance racks, the realm of retail death from which no garment ever returns, a double-death really as everything we sold was already-dead, at best already-almost dead: the false hope of luxury, the false luxury of hope. Why did I seek the living among the dead?

Notes

1. And to a lesser extent from also its Water Tower Place store, north of the State Street store on Michigan Avenue./p>

2. Karl Marx, Critique of Hegel’s “Philosophy of Right”, trans. and ed. Joseph O’Malley (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970), 131.

3. Pew Research Center, Religious Landscape Study, 2014.

4. “MarketLine IndustryProfile: Global Luxury Goods,” Nov., 2021. For comparison, the U.S. car industry had revenues over $620 billion in 2021.

5. CDG, Comme des Garçons Play, Comme des Garçons Homme, Comme des Garçons Homme Plus, Comme des Garçons Homme Deux, and Comme des Garçons SHIRT.

6. Nancy L. Ross, “Waterford Crystal Breaks Tradition,” Rockford Register Star, October 5, 1991, C1.

7. Ashok Som and Christian Blackaert, The Road to Luxury: The Evolution, Markets, and Strategies of Luxury Brand Management (Singapore: John Wiley, 2015).

8. 225,000 square feet on the low end. See Annual Report of Marshall Field and Company, Year Ending January 31, 1974.

9. According to the 2000 Decennial Census: 11th in educational attainment (bachelor’s degree, by percent); last in educational attainment (doctorate degree, by percent); 10th in high school dropouts (by percent); 10th in unemployment (by percent); last in of households with six figure incomes (by percentage); last in median household income; last in average household income; 11th in per capita income; and 2nd for percentage of population living in poverty (only Chicago had a higher percentage of people living in poverty).

10. See Sina Dubovoj and Pamela L. Shelton, “Dayton Hudson Corporation.” In International Directory of Company Histories, edited by Jay P. Pederson, 135-137. Vol. 18. Detroit: St. James Press, 1997. In a 2004 government report, Field’s was classified at the highest level of luxury, alongside chains like Neiman Marcus, Nordstrom, Barney’s, and Saks Fifth Avenue.

11. $53,9704 for the Rockford SMSA, compared with $56,644 for the nation. The Rockford SMSA comprises Boone County, Ogle County, Stephenson County, and Winnebago County. The county in this SMSA with the highest average household income was Boone County, with $61,589; compare that with Du Page County, with an average household income of $86,077. The only compensating factor I can imagine was Rockford’s vast hinterland, and having grown up in that hinterland I can attest that it was quite normal to drive seventy miles for a trip to a mall, so Rockford’s SMSA probably underrepresents the store’s true reach, but probably does not underrepresent its access to the kind of wealth needed to support a high end department store.

12. And, as the only member of Human Resources, every other metaphorical part as well, its very embodiment, head and body, with a part-time secretary perhaps constituting some minor appendage, an arm or maybe just a hand.

13. Barry Bluestone, Patricia Hanna, Sarah Kuhn, and Laura Moore, The Retail Revolution: Market Transformation, Investment, and Labor in the Modern Department Store (Boston: Auburn House, 1981), 82-87.

14. The locution “give guest service,” or “give good guest service,” was forever tripping off the tongues of store management, always a source of mirth and hilarity to my coworkers and me.

15. I recall that associates perfume, cosmetics, and women’s shoes worked almost entirely on commission.

Bibliography

Barkin, Thomas I., James J. Nahirny, and Evan S. van Metre. “Why Are Service Turnarounds so Tough?” The McKinsey Quarterly, no. 1 (1998): 46–54.

Berg, Maxine BergMaxine. “Luxury Trades.” In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Economic History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Bluestone, Barry. The Retail Revolution: Market Transformation, Investment, and Labor in the Modern Department Store. Boston, Mass: Auburn House Pub. Co., 1981.

Chandler, Susan. “What Do Shoppers Want?” Knight Ridder Tribune Business News, September 25, 2005.

CSG Information Services. Directory of Department Stores. Directory of Department Stores. New York: CSG Information Services etc., 1955.

Diaz, Janette A. “Women in Department Store Work: New Forms of Labor Control and the Limits of Mobility.” Ph.D. diss., University of California, Santa Barbara, 2015.

Dubovoj, Sina, and Pamela L. Shelton, “Dayton Hudson Corporation.” In International Directory of Company Histories, edited by Jay P. Pederson, 135-137. Vol. 18. Detroit: St. James Press, 1997

Ellis, Kimberly. “Protecting Your Brand.” Franchising World 36, no. 8 (September 2004): 18–19.

Esch, Franz-Rudolf, Tobias Langner, Bernd H. Schmitt, and Patrick Geus. “Are Brands Forever? How Brand Knowledge and Relationships Affect Current and Future Purchases.” The Journal of Product and Brand Management 15, no. 2 (2006): 98–105.

Granot, Elad, La Toya M. Russell, and Thomas G. Brashear-Alejandro. “Populence: Exploring Luxury for the Masses.” Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 21, no. 1 (Winter 2013): 31–44.

Hagedorn, Ann. “Apparel Makers Play Bigger Part on Sales Floor.” Wall Street Journal, March 2, 1988.

Helliker, Kevin. “Smile: That Cranky Shopper May Be a Store Spy.” Wall Street Journal, November 30, 1994.

Hennigs, Nadine, Klaus-Peter Wiedmann, Christiane Klarmann, and Stefan Behrens. “The Complexity of Value in the Luxury Industry.” International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management 43, no. 10/11 (2015): 922–39.

“Is It Love or an Identity Crisis?: Danger of Split Personality in Brand Marketing.” Strategic Direction 31, no. 6 (2015): 9–11.

Kaplan, Albert A. Careers in Department Store Merchandising. New York: H.Z. Walck, 1962.

“Luxury Goods: The Price of Luxury.” Brand Strategy, November 10, 2008.

“MarketLine Industry Profile: Global Luxury Goods.” MarketLine, November 2021.

“MarketLine Industry Profile: New Cars in United States.” MarketLine, January 2022.

Marshall Field and Company. Annual Report for Year Ending January 31, 1974.

---. Rule Book

---. Work Simplification: The Pattern for Improving Work Methods. March 11, 1948.

Merlo, Elisabetta, and Mario Perugini. “The Revival of Fashion Brands between Marketing and History.” Journal of Historical Research in Marketing 7, no. 1 (2015): 91–112.

Myerly, Scott Hughes, and Tamara L. Hunt. “Holidays and Public Rituals.” In Encyclopedia of European Social History, edited by Peter N. Stearns, 185–200. Detroit: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2001.

Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm. On the Genealogy of Morality. Edited by Keith Ansell-Pearson. Translated by Carol Diethe. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Pew Research Center. Religion & Public Life Project, 2014.

Ross, Nancy L. “Waterford Crystal Breaks Tradition.” Rockford Register Star, October 5, 1991.

Roush, Matt. “Hudson’s Aims Sales Help at Those Who Want It.” Crain’s Detroit Business 13, no. 16 (April 21, 1997): 21.

Sheldon’s Major Stores and Chains and Resident Buying Offices. Fairview, N.J: Phelon, Sheldon and Marsar, 1994.

Som, Ashok, and Christian Blanckaert. The Road to Luxury: The Evolution, Markets, and Strategies of Luxury Brand Management. Singapore: John Wiley and Sons, 2015.

Stankeviciute, Rasa, and Jonas Hoffmann. “The Impact of Brand Extension on the Parent Luxury Fashion Brand: The Cases of Giorgio Armani, Calvin Klein and Jimmy Choo.” Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, December 12, 2012.

Veverka, Mark. “A Down Field’s Heads Upstream.” Crain’s Chicago Business, November 13, 1995.

Xuemei, Bian, and Haque Sadia. “Counterfeit Versus Original Patronage: Do Emotional Brand Attachment, Brand Involvement, and Past Experience Matter?” Journal of Brand Management 27, no. 4 (July 2020): 438–51.