A Guide to Organizational Administration, Part Two

An organization is impossible without division. We begin with an undifferentiated group of people, and we divide them: person A goes here and dose this work; person B goes there and does that work; and so forth. Organization is both the action of organizing, or dividing and sequencing, and the result of that action, which is the highly functioning corporate body that functions highly because it is organized.1

Our humble institution is an organization, and as administrators our concern must be not only with outcomes, but with the labor necessary to produce those outcomes. A highly functioning labor force depends upon the division of that labor force.

The first division of labor was the division of the mind into the conscious and the unconscious, organizing the mind and enabling it to function at extremely high levels of productivity.2 Like the mind, the workforce is continuously divided and subdivided into ever finer areas of specialization.

These divisions create POWER that the organization uses to further its objectives.3

The division of the mind is not unlike the division of the atom, releasing previously unimagined quantities of power. And what, really, is the splitting of the atom but its division and subdivision? And what really is that but the REDIRECTION of sub-atomic particles? Redirection and INDIRECTION are essential to organizational administration.

Many organizational administrators mistakenly believe that their function is to maximize efficiency. This belief is an error. Their function is to maximize the amount of power available to the organization. Not all efficiencies create power, and not all power depends on efficiencies.

Sometimes power can be generated by what appear to be inefficiencies. This process is achieved through a combination of techniques, including indirection, redirection, and COMPARTMENTALIZATION.

Indirection is related to redirection, but is more specifically a technique for achieving a net increase of power by sacrificing short term efficiencies. Not all redirections are indirections.

Indirection is the process of diverting the AGENT (usually a person who performs a TASK) from the shortest, quickest, and apparently-most-efficient path between two POINTS.

The movement of the agent from one point to another is a task or CIRCUIT.

Agents, points, and tasks can all be concrete or abstract.

Each task is a circuit within a larger network of tasks or circuits, and the movement of agents along these circuits is called WORK. Completed work becomes a quantity of power available to the organization.

A task or circuit can be concrete (the agent scoops a serving of mashed potatoes onto a cafeteria tray) or abstract (the agent reads a memo and moves from a state of unknowing to a state of knowing). The satisfaction of an instinct is the most basic example of a task, but that need hardly concern us as organizational administrators. Suffice it to say, these tasks, or circuits are the most basic human activity, and can be manipulated (indirection, for example) and combined (workflows, for example) to achieve highly leveraged outcomes.

To repeat: not all efficiencies generate power.

To repeat: power can be generated by what appear to be inefficiencies.4 This process is called indirection.

Indirection is a form of redirection that has been engineered to maximize the amount of power available to the organization by sacrificing short term efficiencies.5

To repeat: the path between two points is a task, and can be likened to a circuit.

People not trained to be administrators will naively assume that B always must follow A.

In the above example, an untrained administrator will assume that efficiency must be measured by the RESOURCES consumed in the process of completing a single, discrete task.

Getting from A to B is a task.

To repeat: a task can also be called a circuit.

Untrained administrators tend to forget that every task is part of a larger system that constitutes the organization's actual work.

It's the power generated for the entire system (or organization) that must be the administrator's main concern, not the efficiency of discrete tasks within the system.

When shown the above, people will usually assume that the most efficient way of completing the task (or circuit) of moving from from A to B will a direct line, as shown above.

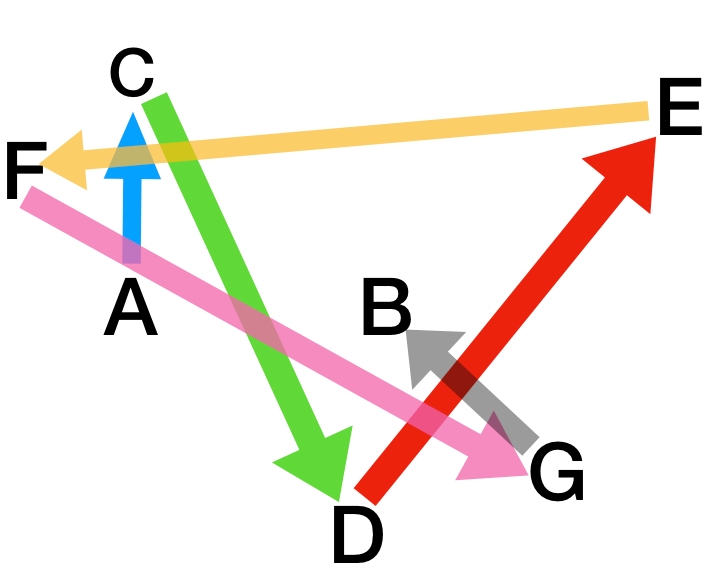

However, greater power might be realized for the organization by implementing a series of indirections as shown below:

The above expresses multiple symbolic orders using a single symbol system.

This form of indirection is technically (and all aspects of modernity are technical) MISDIRECTION because it diverts the agent from the shortest, quickest—hence, most "efficient"—path between two points.

People are wrong to assume that B must always and immediately follow A.

Sometimes B is preceded by C, D, E, F, and G.

Consider the fundraising we discussed in the previous lecture. To obtain donations of money, the circuit is A to B: an Agent wishes to go from point A to point B, where point A is a point of wishing to obtain a donation from a potential donor, and point B is the point where the potential donor donates money. It may seem as though the most efficient method of obtaining a donation is to contact the donor, and ask for money. Anyone who actually does fundraising work, however, will tell you that this highly efficient method is also highly unproductive. Am I right Cassie? [Laughter] A fundraiser can spend years cultivating a donor before actually making the ask.

Now, we can also see this same phenomenon in sentences. A sentence is a mechanism for organizing information, a circuit along which the reader's attention travels towards some goal, from subject to predicate, and like all organizing systems, the sentence will sacrifice short term efficiencies in order to realize a long term increase in power. It achieves this objective by using a series of indirections and misdirections. Consider this basically unremarkable sentence from Reed-Kellogg:

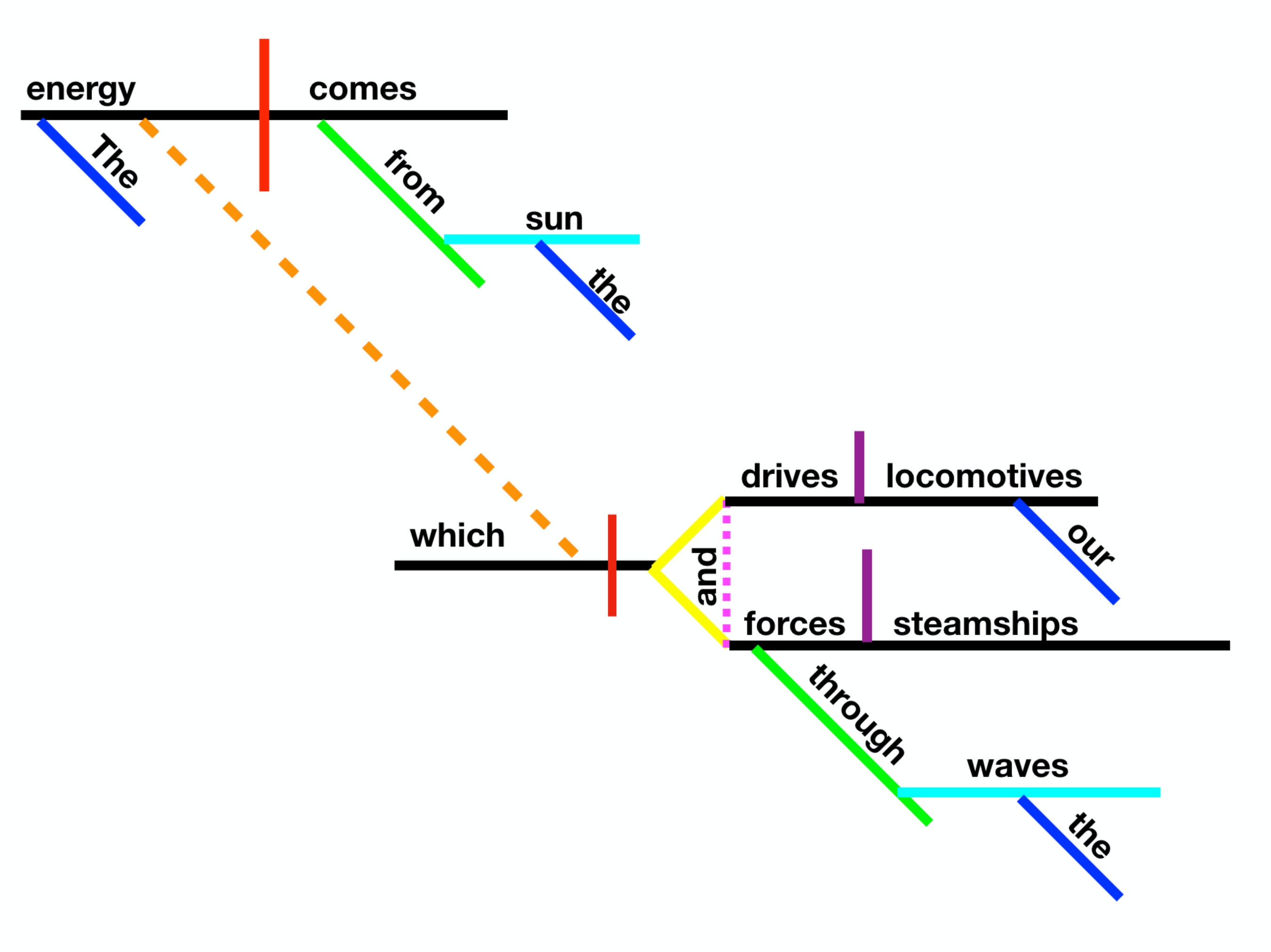

A Reed-Kellogg sentence diagram enables us to decompose this sentence and see the many indirections it employs:

If sentences really were about directness, then we would simply have our subject and our predicate: energy comes from the sun. But that's not really what the sentence is about, is it? The real work has been compartmentalized and the Reed-Kellogg diagram reveals this compartmentalization. Almost as though the author had hidden the most important information, but of course it isn't hidden because it discloses itself to us as we traverse the sentence, and it isn't the most important because the most important thing is the relationships between, and sequencing of, the sentence's grammatical components.

The sentence diagram models the proper functioning of an organization: compartmentalization and indirection. Each part of the organization concerns itself only with conforming to the grammar that governs it. It is the job of the administrator to organize and sequence these parts so as to achieve the maximum potential of power.

Footnotes

- If the Bible is to be believed, the whole world was created through divine acts of division!

- Compared with other animals.

- The foremost objective of the organization, of course, is to perpetuate itself.

- A phenomenon that always eludes so-called efficiency experts who are forever demanding the elimination of waste in government: the purpose of government is not efficiency or even conservation of resources. The purpose of govern is to govern; in other words, to wield power.

- Again, please note the parallels between the functioning of the mind and the functioning of the organization. As Freud wrote in Civilization and Its Discontents, "Sublimation (or displacement, redirection) of instinct is an especially conspicuous feature of cultural development; it is what makes possible higher psychological activities: scientific, artistic, and so forth" (Trans. James Stratchey).